Bayesian evaluation for the likelihood of Christ's resurrection (Easter 2020)

This was the state of the "Bayesian evaluation for the likelihood of Christ's resurrection" post, as of Easter 2020. This post will remain unchanged, while the linked post above will have further edits.

I also put up a Facebook post on that date, which is essentially the same as the 2019 Facebook post. The offer mentioned there still stands.

I didn't write an addition to the "epilogue" section this year. I feel like I'm still refining the 3rd draft, but I'm getting more ideas of additional things I can put in. I may have to start pruning all but the very good ideas now. We'll see. Here's to great progress by the next Easter!

Contents:

PART I: The simple version of the argument

Chapter 1: The priors

- The prior odds against a resurrection

Chapter 2: The evidence

- The nature of the evidence for Christ's resurrection

-- The Bayes factor for a human testimony

Chapter 3: Assembling the basic argument

- Is the evidence enough?

- There is far more than enough evidence to overcome the prior

PART II: Double checks

Chapter 4: Double checking our evaluation of human testimonies

- Why are we double checking? What are we double checking?

- Double check: the Bayes factor of a human testimony.

-- The frequency of lies

-- Car accidents

-- Human death

-- LinkedIn claim

-- Fake 9/11 victims

-- One red dot in a million

-- One in a million events happen every month

-- Video of a lottery winner

-- Summary of the findings

-- The strength of a human testimony is firmly established and understood.

-- The first step in a testimony: the inception of the idea

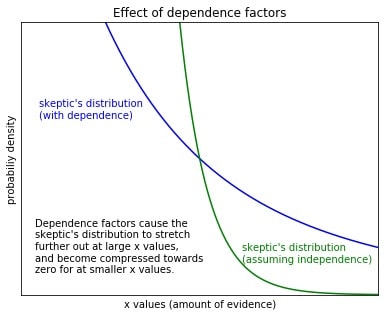

-- The "human honesty" step, and dependence factors in multiple testimonies

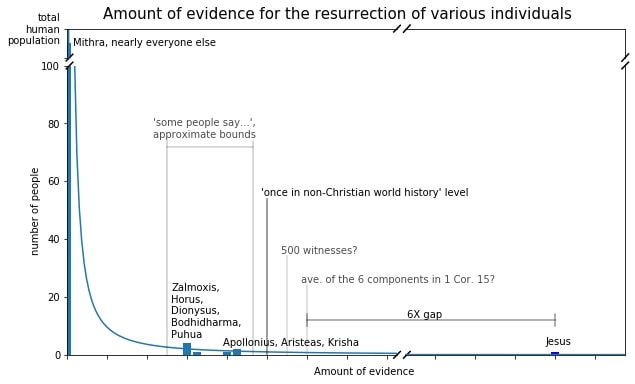

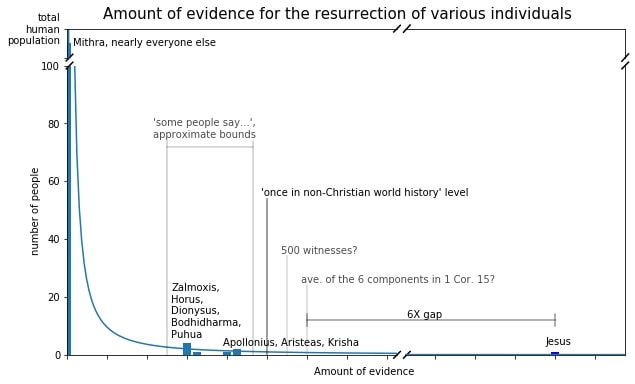

Chapter 6: Double checking against the other resurrection reports in history

- Can naturalistic explanations account for the resurrection testimonies?

-- Well, can you demonstrate that empirically?

- The New Testament, and what it would take to match its resurrection reports

-- Peter, James, Paul

-- Apollonius of Tyana

-- Zalmoxis

-- Aristeas

-- Mithra

-- Horus and Osiris

-- Dionysus

-- Krishna

-- Bodhidharma

-- Puhua

- Our previous calculations are fully validated

PART III: Answering simplistic objections

Chapter 7: The usual barrage of objections

- What, if anything, is wrong with the previous argument?

-- Is the prior too large, especially for a supernatural event?

-- "But Science!"

-- Can human testimonies be trusted?

-- Can the New Testament be trusted?

-- Could the disciples have been genuinely mistaken?

-- Or actively deceptive?

-- Or actually crazy?

-- Or some combination of the above, or something else entirely?

Chapter 8: The strength of a Bayesian argument: why none of these objections work

- The nature of Bayesian arguments.

PART IV: Addressing all possible alternatives

Chapter 9: Time to address the crackpot theories

- The next steps

- Examining crackpot theories, in general

Chapter 10: The "skeptic's distribution".

- Using the historical data to construct the skeptic's distribution

-- Assigning numerical x values

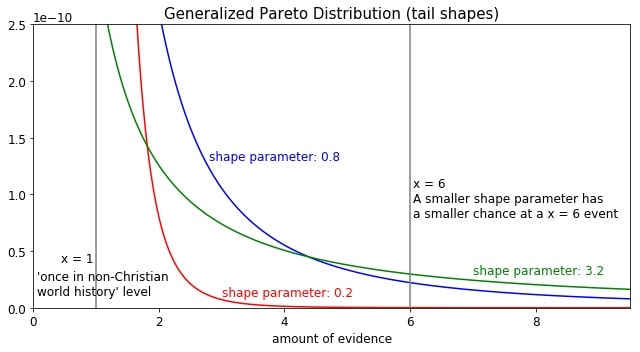

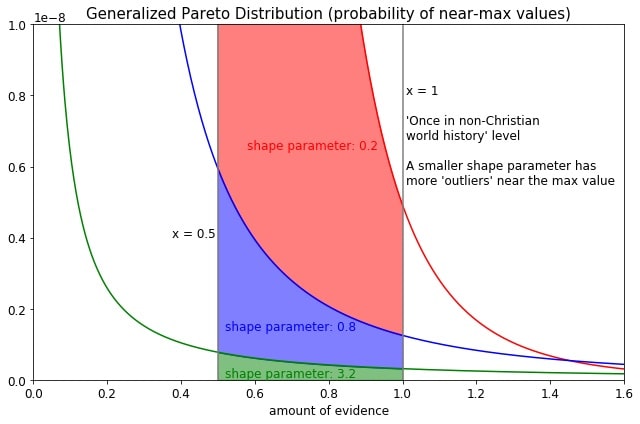

-- What should be the form of this "skeptic's distribution"?

-- Details of the distribution: generalized Pareto distribution and its parameters

-- But how should we determine the value of the shape parameter?

-- Defining "outliers"

-- Back to determining the shape parameter

- The alternate hypothesis and its distribution

- Empirical evidence from other historical figures in ancient history

-- The Buddha

-- Confucius

-- Socrates

-- Tiberius

-- Arguments using the New Testament itself

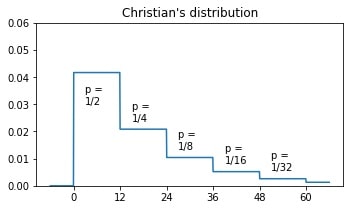

- The exact mathematical form of the "Christian's distribution"

-- The robustness of the Christian's distribution

-- Simulation and code: The number of "outliers" decides the case.

-- Putting Jesus's resurrection over the top: the list of outliers

Chapter 13: Tuning the "ratio of distributions" approach

- We were far too generous for the "skeptic's distribution"

-- The power law distribution

-- The boundaries of outliers

-- A better estimate of the probability

- Defenses against crackpot theories built in to Christianity

-- Apostle Paul

-- The "final" odds for the resurrection

PART V: More double checks

Chapter 15: Double check: reports of miracles in other religions

- The stance on non-Christian miracles

- Ichadon

- Vespasian

-- "Something happened" vs. "a miracle happened"

- Splitting the Moon

- Accounts in Josephus

-- Honi the Circle-drawer

-- Eleazar the exorcist

-- "Something happened" vs. "a miracle happened", again

Chapter 16: Double checks for the "ratio of distributions" approach

PART VI: Challenge and conclusion

Chapter 17: The final challenge: replicate the results

- The rationale for this challenge

Chapter 18: Conclusion and epilogue

- Conclusion

more ideas:

go straight into the strongest argument for 1e8 being the strength of a human testimony?

rewrite section to fully describe the complexity of human trustworthiness, or at least very explicitly say so. - switch chapters 4 and 5.

shorten the summary of the strength of a human testimony bayes factors examples?

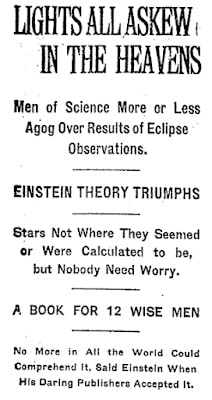

better priors? the general relativity argument takes care of that

independence investigation: get into the mind of individuals.

- coin flips for fair/double heads: still dependent because of truth itself. So it should still affect things even for Paul's independence.

- demonstrate that order of consideration of facts don't matter

- how does reward/risk/effort change that?

check end

The prior odds against a resurrection

What is the probability that Jesus rose from the dead?

Here I'm going to construct a rather foolish partner to advance certain arguments. This is just a rhetorical device. I have to be careful to not commit a straw man here, nor do I wish to insult anyone. I don't intend to imply that anyone actually thinks like my partner. But while he's too foolish to actually stand in for any specific person, he can therefore be useful, by standing in as the lower bound on what a reasonable person may think. Please just understand him as the artificial rhetorical construction that he is.

Now, my foolish partner may say, "the probability that Jesus rose from the dead is zero. What's there to talk about?" But by doing so, he has committed the cardinal sin in Bayesian reasoning. Any real, non-theoretical probability CANNOT be absolutely zero or one. Think about what a zero probability value means: this represents a state of mind where absolutely NOTHING - no amount of possible evidence - can alter their beliefs. There is no reasoning with such a person.

I am very certain that the sun will rise tomorrow. I may be 99.9999...% certain, but I cannot be 100% certain. That tiny difference between 99.9999...% and 100% represents possibilities like a super-advanced alien race stopping the rotation of the earth, or me being momentarily confused about what is meant by "the sun". And I am not 100% certain, because I can, at least in theory, be shown evidence that such an alien race exists, or that I had momentarily confused "the sun" with "the north star".

My partner may then say, "well, the probability may not be actually zero, but it's very close to it. Like, 0.000.....001%. Nobody has ever come back from the dead before." But actually, isn't that the very thing we're talking about? Whether Jesus had come back from the dead? Furthermore, it's presumptuous to think Jesus was just like everyone else, that he wasn't special in any way. Even if nobody else came back from the dead, we would need to do some additional thinking in the case of Jesus.

My partner would reply, "see, that's just special pleading. I don't see why Jesus should be special. Empirically, people do not come back from the dead. Therefore it's also highly unlikely that Jesus came back."

At this point, I'm going to simply give away the point about whether Jesus was special or not. I obviously believe that he was - but quite frankly, the argument for the resurrection is so strong that I can just handicap myself in several different ways like this without materially affecting the conclusion. I'll be doing this multiple times throughout this post.

Now, back to how many people came back from the dead, "empirically": how many different people have you seen die and stay dead? Remember, we're talking about "empirical" evidence here, meaning that we only count people that you, yourself, have seen die in person. For many people, that number is probably zero. It might be one or two - maybe you've seen a grandparent pass away. Maybe more, if you're a healthcare worker or something like that.

My partner may say, "Even if I didn't see someone die in person, if there was a real resurrection, it would be all over the news. And there hasn't been any such reports, because people do not rise from the dead."

Well, at this point, my partner is begging the question on whether there has in fact been such reports, and is becoming slippery about what "empirically" means. But again, I will simply handicap myself and give away these points. "Empiricism" in the sense of "I only believe what I can see" is fundamentally flawed, anyway (It's self-defeating). So let's adopt a more reasonable form of empiricism, and say that news reports are enough, and a direct observation is unnecessary. So, how many people have been covered in the news that you've seen? Thousands? Millions? If the argument is that Jesus was no different than these thousands or millions of other people, then I freely acknowledge that this does in fact establish an upper bound on the probability of the resurrection. However, this does NOT prove that the probability is zero, no more than a dozen coin flip of heads proves that the coin will always land heads. Instead, it merely says that the probability for the resurrection is likely to be below a certain level.

For example, say that you've examined a thousand swans, and they all turned out to be white. You want to use this fact to investigate the existence of a black swan. Now, your study of a thousand white swans don't prove that black swans are an impossibility, with a probability of zero. Instead, it impose a prior probability against a report of a black swan: there is only somewhat less than 1/1000 chance that the reported swan is actually black. If you've instead examined a million swans that were all white, then your probability of observing a black swan would correspondingly drop to around 1/1 000 000 as the upper limit. (For the technically minded: I'm starting with the Jeffreys prior of Beta(1/2, 1/2), then adding in the number of observed "white swan" events to approximate the "black swan" probability distribution. This is standard practice.)

Now, the modern media is pretty comprehensive, so my partner may say, "The world news covers many millions of other people. And none of them have come back from the dead. So the chance that Jesus came back from the dead is, at best, one in a million. That's basically zero. How could you believe in something that has only one in a million chance of being true? That's irrational."

Well, one in a million is a pretty small probability. But actually, I think we can just go ahead and say that out of the entire world population of 8 billion people, none of them are going to be raised from the dead. So, the probability for the resurrection has now dropped to 1 in 8 billion. I'm just giving away everything here. I've almost dropped the condition about an "empirical" probability. I'm making a blanket statement that absolutely nobody in the world, independent of anything that may be know about them, will rise from the dead. So, if we apply this general "observation" to the likelihood of Jesus's resurrection, that probability must be below 1 in 8 billion.

My partner may respond, "Um... So now you're making my argument for me. So yeah. The probability of the resurrection is less than 1 in 8 billion. Obviously you can't believe in something that unlikely to be true. This is why any naturalistic explanations must always be preferred to a supernatural one in these discussions of miracles, because the supernatural is always so unlikely."

Oh, but I'm not done yet. I'm going to give away even more of the argument. Why not just drop all pretense of an "empirical" probability? Why not say that everyone who has EVER lived - about 100 billion people in total - have all died, without a single one of them being raised from the dead? Forget saying anything about "empirical observations". Forget any semblance of reasoning from our direct experiences. Ignore anything about reported resurrections. I will simply grant that every single one of these 100 billion people have died and stayed dead. And against the weight of those 100 billion people, we'll estimate the probability of Jesus's resurrection. According to our previous line of thinking, this puts that probability at 1 out of 100 billion.

My foolish partner may say, upon the strength of this evidence that I have made up for him, "One in a hundred billion! Do you know how unlikely that is? That's 1 out of 100 000 000 000. That's a probability value of 0.000 000 000 01. That's basically zero. Just concede the argument - it's virtually impossible that Jesus rose from the dead. Absolutely any naturalistic explanation is going to be more likely than that."

Well, should I just concede? That does seem like a very impressive number, no? How did we even get to this point? I started with the "Nobody rises from the dead, so Jesus also didn't rise from the dead" argument. I then stretched it to its strongest form, to include the entire current world population. I ignored all objections about the specifics in Jesus's case, or the exact meaning of "empiricism". But all that wasn't enough - I wanted it to be stronger still. So I then added some made-up stuff on top, to strengthen it even further, to a level beyond any possible empirical justification.

So now, as it stands, the probability of Jesus actually having risen from the dead is 1 out of 100 000 000 000 - essentially zero. That's game over, right? How could I, or anyone, believe in something so unlikely to be true? How could any hypothesis with a probability of 0.000 000 000 01 ever be taken seriously?

"Um... so yeah. What are you doing?", my partner may ask.

You'll see. Read on, and you'll behold and understand the power of evidence.

The nature of the evidence for Christ's resurrection

That probability value for the resurrection - 0.000 000 000 01 (which can be written as 1e-11, employing scientific notation) - is a prior probability. That is, it's a probability based on the background information, taking into consideration the fact that Jesus was human, and that humans don't rise from the dead.

However, it is just the starting point. To proceed from this point on, let us first consider some scenarios - they may seem like a detour, but we'll be back on track soon enough.

Let's say that you're meeting someone new. You talk for a while, and the conversation turns to birthdays. You reveal that you were born in January, and your new friend says, "Oh, really? I was born in January too!" He seems earnest - he's not obviously joking, sarcastic, or ingratiating. From the little you know of him, he's not any more likely to be delusional or deceptive than anyone else.

Now, based only on his earnest word, would you be willing to believe that your new friend really was born in January? Note that I'm not looking for 100% certainty here. A willingness to entertain the idea, to give it a 50-50 shot of being true, is all that's required.

Also note that I'm not asking whether this event is likely to happen. Obviously, the probability that you and a random other person shares the same birth month is about 1/12, so it may be said to be "unlikely". Rather, I'm asking whether you would believe this person, given that this unlikely event has already occurred.

So, how would you respond? Would you say, "I find your claim to be highly dubious. There's only 1/12 chance that you were born in the same month as me"? Or would you simply reply, "Oh, hey, that's neat!"

I'm going to assume that you're willing to believe your new friend. I think you'll agree that it takes a special kind of jerk to say "I don't believe you. You must be lying or mistaken. It's just too unlikely for us to share the same birth month". In that case, what if it had turned out that you share the exact same birthday? You mention that you were born January 23rd, and he claims the same. Would you still believe him?

Now let's tweak the scenario a bit: what if he learns the birthdays of everyone in your family, and then claims multiple matches? Say that you had written down a list of these family birthdays, and your new friend happens to come across it. He then says, "hey, we share the same birthdays - and our moms do too!" Would you believe him? And what if he had made the claim for the first three people on the list - you, your mom, and your dad?

At what point does such a claim become too unlikely for you to believe? If your friend had made the "shared birthdays" claim for the first four, five, or six people on your list - siblings, grandparents, cousins - at what number would you have said "I cannot believe this - this is too unlikely to be true", in spite of your friend's sincere and insistent claim?

Decide on an answer, and remember it. Write it down somewhere. We'll come back to this answer soon. Make a firm statement like, "I would be willing to believe up to 3 shared birthdays - myself, mother, and father - but if he claimed 4 or more I would begin to be skeptical".

Let's try another example. Let's say that you run into an acquaintance whom you haven't seen in a while. You exchange greetings and ask how he's been, and he excitedly tells you - "Guess what! I've actually won the jackpot in the lottery last month! I'm rich!" As before, he seems earnest - he's not obviously joking, sarcastic, delusional, or deceptive. Would you believe him, based only on his earnest word? Again, only a willingness to entertain the idea, just granting a 50 - 50 chance of it being true, is all we're looking for here. Would you give him at least even odds that he's telling the truth?

And if you would, how about if he claimed to have won two consecutive jackpots? How about three? At which point would you say "That's just too much for me to believe"?

Next, let's switch over to other gambling games. Say that a friend claims to have had a very lucky night at the card tables. He says that he got a royal flush in a 5-card stud poker game. Would you believe him? What if he claims to have gotten two royal flushes last night? What if he claims three? At what point would you say, "I don't believe you. You seem earnest and all, but the chances of that happening are just too small"?

How about if he were playing Texas Hold'em, and claims to have had multiple pocket aces? Say that he claims to have had two, three, four, or five pocket aces last night. At what number does it become too unlikely to be true, despite your friend's sincere claim?

We can ask similar kinds of questions in many different ways. What if someone claims to be born naturally as a part of twins, triplets, quadruplets, or quintuplets? What if someone claims to have recently been struck by lightning? Or that they were a victim of two or three such strikes?

Remember, in all these cases, that we're not looking for certainty. Just a willingness to entertain the idea - a 50-50 likelihood for the statement is true - is enough to say that you'd believe your friend. Also, we're not asking whether these scenarios are likely; rather we're asking if you'd continue to believe this earnest person, despite the fact that he's claiming that an unlikely event happened.

Answer these questions. Give a specific number in each case: we want answers like "four royal flushes" and "two lightning strikes". Write them down somewhere - we'll come back to them later.

Now, we'll turn to the question of Jesus's resurrection.

The Bayes factor for a human testimony

Recall that we had rather generously put the probability against Jesus's resurrection at a prior value of 1 out of 100 billion (that is, 0.000 000 000 01, or 1e-11). At such extreme values, "probability" is nearly synonymous with "odds": so the prior odds against Jesus's resurrection is 1e-11.

Recall also that this was only the starting point. It does not take into account any evidence we have specifically about Jesus's resurrection. Remember Bayes' rule: the final, posterior odds is the prior odds times the Bayes factor, which is the ratio of the likelihoods of each hypotheses generating the evidence. So the number we have now is just the prior odds. We now need a numerical value for the Bayes factor of the evidence, and then we can get our posterior odds.

But what kind of evidence is there for Christ's resurrection? And how could it possibly overcome a prior odds of 1 to 100 000 000 000 against it? Well, as for the evidence, we have the writings of the New Testament, where Jesus's resurrection and his follower's testimonies are documented. Okay, but is this "evidence" any good? How can we put numerical likelihood ratios to these things?

What we need is the numerical strength of a human testimony, of the type that Jesus's disciples gave. As it turns out, we can actually get a not-unreasonable, order of magnitude estimate of this value. Remember your answers to the probability questions in the previous section? I hope you have them written down or otherwise recorded, because we will use them to calculate the Bayes factors that you would personally assign to a human testimony that's making unlikely claims.

Let's use my personal answers, given below, as an example for how to do these calculations. These are my gut answers to the questions, before doing an actual probability calculations. Remember, "believe" here means that I'm willing to give at least even odds (50/50 chance) on the claim. It doesn't mean certainty, and it doesn't mean that I'd stop looking for more evidence. It only points to how much I'm willing to adjust my beliefs based on someone saying "yes, I know it's unlikely, but it really happened".

For the shared birthday question, I would easily believe that my friend shared a birthday with me. I would also not have any real problem believing that our mothers also shared birthdays. At three people - myself, mother, and father - I would start becoming skeptical, but would probably give my friend the benefit of doubt. Starting with four shared birthdays in the family, I would start leaning more heavily towards skepticism.

On winning the lottery, I would not really doubt that my friend won the lottery. I would start doubting if he says that he won two consecutive lotteries.

On getting a royal flush, I think I could almost believe that my friend got two such hands in a very lucky night at the table. I feel like three would be entering the realm of the fantastical, and I would doubt my friend at around this number.

On pocket aces, I would be willing to believe that my friend had up to four or five pocket aces in a lucky night of Hold'em.

On the multiple births, I would not have any real problems believing that someone was a part of natural quadruplets. A claim to be in a quintuplet would start to cause a little bit of doubt to me, and a claim of sextuplets would need additional evidence.

On being struck by lightning, I actually had someone around me claim that this had recently happened to her. I had no problem believing it. Even if she had claimed two such accidents I don't think I would have really doubted her. If she had claimed three, I would start to be skeptical.

Now, calculating the numerical probability values for all these things is pretty straightforward:

The probability of sharing a single birthday is 1/365, or 1/3.65e2. The probability of sharing the three birthdays for your family is then simply this number cubed - 1 in 4.86e7.

The probability of winning the lottery varies by exactly which lottery you're talking about, but the odds for the jackpot are generally somewhere around 1 in 1e8.

The probability of getting a single royal flush is 1 in 6.5e5. The probability of getting two in two hands is therefore this number squared, 1 in 4.2e11. We can then take it down by a couple orders of magnitude, to account for the fact that there's dozens of hands played in a poker night. That gives us something like 1 in 1e9 for the odds.

The probability for getting pocket aces is 1 in 221. Getting five would then be 1 in 5.3e11. Taking it down again by several orders of magnitude to account for multiple hands, that brings us to something like 1 in 3e7.

The probability of natural quadruplets is about 1 in 1e6, and for quintuplets it's about 1 in 5.5e7. We'll split the difference here and call it 1e7.

The probability of getting struck by lightning in a given year is about 1 in 1e6. If we count "recently" as the last 5 years, that would bring it down to 1 in 2e5. Getting struck twice would then be 1 in 4e10, then maybe take off an order of magnitude for possible dependency factors to give us 1 in 4e9.

So, looking at the final numbers above - 1/4.9e7, 1/1e8, 1/1e9, 1/3e7, 1/1e7, 1/4e9 - we seem to be getting a reasonably consistent estimate for how I value the strength of an earnest, personal testimony. There are a lot of small details we can go over again (how many hands of poker did you play last night? Is your friend someone likely to play the lottery, or to be outdoors during a thunderstorm?), but these will largely be random, small, unknowable effects that will get washed out in this order-of-magnitude calculation.

So, we'll take the geometric mean of the above values(1/1.3e8), and then conservatively round down to get 1/1e8, or 1e-8, as their "average" probability. In other words, even if an event had only a 1e-8 prior chance of happening, I would be willing to give even odds on that event having occurred based on someone's earnest, personal testimony.

So such a testimony will shift the odds from 1/1e8 to 1/1. Or, to put it yet another way: the typical Bayes factor for an earnest, personal testimony about an unlikely event is around 1e8. That is my numerical value for the strength of a human testimony, under the conditions specified above.

It is important to note that this number is not something that I just made up. The math that gives this value is described above in its entirety. What answer did you get when you plugged in the numbers? That is the number that you, personally, must be willing to assign to the strength of a personal testimony, if you are to be consistent. I believe that most reasonable people will be within a couple of orders of magnitude of my answer.

Double checking the Bayes factor: Lottery winner

Now, we don't want to just take someone's personal answers and simply run with it - even if that someone is ourselves. It's also possible for a sufficiently hardheaded skeptic to simply say "I won't believe anything that anyone tells me". For these reasons, it's important to double check our answers with empirical evidence, and to correct any mistakes we've made. Fortunately, there are a number of different ways to do that.

Consider this thought experiment: some time in the future, you find yourself telling someone, "I just hit the jackpot in the lottery". You are being sincere and insistent. Now, what is the probability that you're telling the truth here?

Again, the odds of winning the lottery is about 1e-8. So if you agree with my assessment that personal testimony should be valued at a Bayes factor of around 1e8, then you are about equally likely to be telling the truth or lying in this scenario. However, if you disagree with that assessment - for example, if you think that personal testimony should only be valued at 1e6 - then you're saying that the posterior odds of you having won the lottery is still only 1/100, and so you're 99% likely to be lying in that scenario. Which is it?

And what if we were to expand this to people beyond yourself? Imagine investigating a random sample of people who claimed to have won the lottery. Remember, we're only counting earnest, insistent, personal claims to the jackpot. What fraction of them are telling the truth? How many of them are actual lottery winners? If you say "maybe around half?", then you're agreeing with my Bayes factor of 1e8. If you want the Bayes factor to be 1e4 instead, then you need 99.99% of these people to be liars. Meaning, you need to find me 10 000 liars for every true winner I can find.

Well, fortunately for us, this "lottery liars" experiment has actually been naturally conducted, and we can compare its result with our numbers. On January 13, 2016, the Powerball lottery produced the largest jackpot in history (as of the time of this writing): 1.6 billion dollars. This jackpot ended up being split three ways. But - were there people who lied about having won this jackpot? As a matter of fact, there were. Several people on social media claimed to be a winner, presumably in an attempt at some quick, cheap fame. How many such people were there?

I couldn't get an exact number for the number of Powerball jackpot liars, but we can still get a sense, an order-of-magnitude estimate. Snopes, for example, mentions two people by name, and "several" or "numerous" others. Another report claims "a number" of similar hoaxes. So - it sounds like maybe ten people lied about winning the jackpot? It's certainly not in the hundreds or thousands.

How does that compare with the estimates from my probability calculation? Well, the odds of hitting the jackpot in Powerball are about 1/3e8. However, people may buy multiple tickets - which many people certainly did on such a well-publicized jackpot. In the end, there were 3 actual winners, out of the total American population of 3e8 people. So the prior odds for a specific person in the United States being a winner was 3/3e8, or 1/1e8.

Now, if the Bayes factor for an earnest personal testimony is 1e8, then the posterior odds is just the product of 1/1e8 and 1e8, which is 1. That translates into 1 actual winner for every liar. So, given that there were 3 actual winners to the jackpot, we should expect around 3 liars - and that is roughly what we actually appear to have, within an order of magnitude.

You can again nitpick at this example (the great publicity of this jackpot, the people who made an earnest claim offline, the relative certainty of a short-lived notoriety for lying, etc.) But as an order-of magnitude estimate, the results of this natural experiment are about as good as I can possibly hope for.

We get similar results from other similar calculations: for instance, the Bayes factor for someone claiming a rare and extraordinary position on LinkedIn has a Bayes factor distinctly above 1e7. And a report of a sudden tragic death can be demonstrated to have a Bayes factor around 1e8. And an entirely different approach, used to calculate the Bayes factor of the specific kind of individual testimony found in the New Testament, gives us a Bayes factor of more than 1e9. We will later return to these and many other calculations in great detail. They are all in agreement with our current line of thought, and so they all validate one another.

But for now, let us proceed with the rest of the basic Bayesian argument, using 1e8 as the typical Bayes factor of the kind of testimony we're concerned with. It is certainly not several orders of magnitude less than that.

Is the evidence enough?

Now that we have all the necessary numerical values, we can finally calculate the probability that Jesus rose from the dead.

To begin, I gave the prior odds for Jesus's resurrection as 1e-11. This number was obtained from the argument that "empirically, people do not rise from the dead. Therefore, Jesus also couldn't have risen from the dead." I took that argument, then made it as strong as possible, then gave away everything that it asked for, then gave away even some more things that it didn't ask for, to the point of strengthening it beyond all bounds of empiricism. This number is equivalent to a prior obtained by individually checking and confirming that every single person who has ever existed has failed to resurrect. In other words, this 1e-11 is a smaller odds than anything that any skeptic can reasonably ask for.

Next, we calculated a typical value for the Bayes factor for the relevant kind of testimony - a seemingly earnest, sincere, personal testimony, making an unlikely claim. It worked out to be about 1e8. It's certainly not much less than that.

Now, we simply apply Bayes' rule: posterior odds are prior odds times Bayes factors (the likelihood ratio). So, we'll just look through the New Testament, and see if we can find people who made an earnest, personal claim that Jesus rose from the dead. Let's start in 1 Corinthians 15, because that's a famous passage on the resurrection, recognized even by skeptical scholars as originating within a few years of Jesus's death. It's a good partial summary of the other resurrection-related testimonies in the New Testament. It reads:

For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.

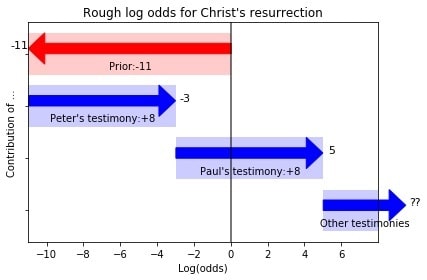

So, who in this passage can be said to have made an earnest, personal claim of Jesus's resurrection? Well, there's Cephas, also known as the apostle Peter. He's a major character in the New Testament, and every one of the numerous accounts of him says that he did, in fact, testify that Jesus rose from the dead. Certainly, that's one witness. The odds of Christ's resurrection after taking Peter's testimony into account is now 1e-11 * 1e8 = 1e-3.

Anyone else we can find here? Well, there's Paul, the author of the very text we're reading, and one of the most prolific writers of the New Testament. He himself says in this passage that the risen Christ appeared to him. Furthermore, Paul was initially a dedicated opponent of Christianity, before his miraculous conversion. So barring some crackpot conspiracy theories, there's little worry about any strong dependency factors which would significantly reduce the impact of his testimony. In fact, his testimony could naturally expect to be anti-correlated with Peter's, but let's just ignore all that. We'll count his testimony at a Bayes factor of 1e8. The odds of Christ's resurrection after taking it into account is now 1e-3 * 1e8 = 1e5, or 100 000 to 1 FOR the resurrection.

Huh, would you look at that. After taking just two witnesses into account, the odds are now in FAVOR of the resurrection. And this is literally using just a fraction of the first passage we chose in the New Testament! Even within this passage, we still haven't taken into account James, or the other members of the twelve disciples, or the other apostles, or the five hundred that are mentioned. And then, we still have the rest of the New Testament to still go through!

What happened? The prior odds was 1e-11 - that's 1 in 100 000 000 000! Wasn't that supposed to be an impossibly small odds? Wasn't it suppose to be insurmountable? Wasn't it something that enabled atheists to simply say, "therefore any naturalistic explanation is bound to be more likely"? Wasn't it a bulwark for skepticism, based on some kind of empiricism? How could it have just... evaporated like that?

That is the power of evidence. Evidence can cause swings in probability that seem ridiculously large to people who are not actually familiar with the mathematics. Did you think that a billion is a large number, or that a probability of one in a billion is too small to ever care about? It is not. In some kinds of math, even numbers like a googol (1e100) can disappear to nothing in just a few lines of calculation. And probability is one example of that kind of math.

Just the other day at my work (Bayes' theorem and probability calculations are part of my day job), a Bayes factor of 1e-10 came up. It merited no comment beyond "that's pretty small". Another time, 1e-40 appeared as a Bayes factor, again with little commentary on its magnitude. Numbers like that are not atypical in probability calculations. Do you realize that, if I specify the order of cards in a shuffled deck of playing cards, that I'm doing so against an odds of 1 to 8e67? That if I hand you a record of a chess game (which can fit on a single post-it note), I'm specifying one out of at least 1e120 possibilities? So, a billion - which is only 1e9 - is not a large number. And the prior odds against the resurrection - which is only 1e-11 - gets completely blown away when it's set against the evidence.

Here, it's important to again note that I'm handicapping the argument for the resurrection. I already mentioned how the prior odds of 1e-11 was far smaller than anything that a skeptic can reasonably ask for. As it turns out, the Bayes factor of 1e8 for a personal testimony is also smaller than it could have been. It's the right value for our general case, but in specific situations it may be far larger. Note the above example of recording a chess game: if you choose to believe that my record of the game is accurate, you're giving me a Bayes factor of around 1e120 for my testimony.

So, as it stands for the moment, the odds are around 100 000:1 in FAVOR of the resurrection, using only Peter and Paul's personal testimonies. The seemingly strong "nobody rises from the dead, so Jesus couldn't either" argument has been fully overcome, with only a tiny fraction of the evidence we have in the New Testament. At this point, the resurrection is already quite probable - but I suppose we might as well finish off the passage we've started on, to see how the odds grow from here.

From here, I'm going to be pretty sloppy for the rest of this calculation, because it just does not matter in the end. The case for the resurrection is just that strong. In particular I'll be setting aside some kinds of crackpot theories for now, which allows me to ignore some kinds of dependence factors. We will address those points more fully later. But for now, this won't affect our conclusion - we're just piling more evidence on top of an already near-certain proposition with the remaining testimonies in 1 Corinthians 15.

So, let's see who else comes up in 1 Corinthians 15. There's James, the brother of the Lord. He's another major character in the New Testament, another major player in early Christianity. We have no doubt that he professed that Jesus rose from the dead. So that's an additional named witness. Taking his testimony into account, the odds of Christ's resurrection is now 1e5 * 1e8 = 1e13 for the resurrection.

Furthermore, 1 Corinthians 15 says that Jesus appeared to "the twelve", and also to "all the apostles", which form two distinct groups. Let's first consider "the twelve". To compute their Bayes factor, we'll go ahead and cut down their number to include only the better-known disciples who are mentioned more often in the New Testament. Say that leaves us with 4 disciples. With some dependency factors and all, let's give each of these disciples a Bayes factor of 100 for their testimony. That value represents a rather low opinion of their trustworthiness: you wouldn't believe such a person even if they told you their own birthday.

Even so, the overall Bayes factor for "the twelve" is still 100^4, or 1e8. If we also give "all the [other] apostles" the same Bayes factor, the odds of Christ's resurrection, after taking these two groups into account, now becomes 1e13 * 1e8 * 1e8 = 1e29.

1 Corinthians 15 also mentions Jesus appearing to "more than five hundred brothers at one time". It's clear that Paul had a specific set of people in mind, as they are part of this early central creed, and Paul mentions that some of these people have died. The number 500, too, is not something anyone just made up - it seems as if the passage is extra careful to mention that some have died, because this may have reduced the actual number of living witnesses to below 500. But let's just ignore all that. Let's pretend that Paul (and the early Christians) exaggerated this number by a factor of ten, so that there were only 50 people claiming to have seen the resurrected Christ. Let's furthermore give them a Bayes factor of 1.5 for their testimonies - meaning you wouldn't trust them to report their own gender correctly. Again, even with these low values, their overall Bayes factor is 1.5^50, which is still well over 1e8. The odds of Christ's resurrection, after taking these people's testimonies into account, is now over 1e29 * 1e8 = 1e37.

Now, as I said there's a lot of sloppiness in the above calculation. The dependency factors need to be handled more carefully, and one should be careful of making claims with numbers like 1e37 as the actual, final odds in a real-world context, for at those levels even the crackpot conspiracy theories can come into play. But really, the fact that we have to even worry about that is a testament to the strength of the evidence. We will come back to all these points later - but what IS completely clear, even at this early point, is that the evidence for the resurrection completely overwhelms the prior odds. Jesus almost certainly rose from the dead.

There is far more than enough evidence to overcome the prior

This brings us to the end of the 1 Corinthians 15 passage. We can go through the remainder of the New Testament, but that'd be lot of work to improve an odds that's already near certainty - so this is a good place to stop for now. What have we achieved? Consider:

We have only used the strength of personal testimonies. That is, we've only used the fact some people have said that they have personally witnessed to the resurrected Christ. We have not yet taken into account any other kinds of evidence, such as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies, or physical facts like the currently empty tomb, or historical facts like Christianity's explosive early growth, or anything else.

We have used conservative numbers in each step of our calculations.

We have only focused on a single passage from the entire New Testament.

We have only considered a rather weak version of a human testimony, like someone being earnest in a single meeting. But the disciples did much more - they were sincere, insistent, and enduring in proclaiming the resurrection, for the rest of their changed lives. Most of them died as martyrs - for making the same claim, with the same earnest seriousness, to everyone they would meet. This elevates their testimony to a whole new level, which we have not accounted for.

And even under these restrictions, the testimonies have easily overcome the 1e-11 prior odds against a resurrection, and have reached posterior odds corresponding to near certainty. If I were to carry out a more complete and reasonable calculation, using all the different lines of evidence that a modern Christian has at his or her disposal, the final odds would further increase still, by multiple orders of magnitude. Jesus almost certainly rose from the dead.

Questions about Bayes rule and human testimony

My claim, at its heart, is very simple: the evidence of the many people claiming to have seen the risen Christ is abundantly sufficient to overcome any prior skepticism about a dead man coming back to life. My argument consists of backing up that statement with Bayesian reasoning and empirically derived probability values.

The emphasis on empirical values is important. Humans are notoriously bad at estimating probabilities, especially when the values reach extreme levels, like 1e-11. Some people, especially when discussing a controversial topic like the resurrection, will just pull their numbers out of thin air. They'll make statements like "I'll grant a 23.599% chance that the disciples went to the wrong tomb". This can sometimes result in some pretty hilarious statements, like someone assigning a 1% chance for a generic conspiracy theory - as if they couldn't imagine anything less likely than a 1% probability.

This is why having an empirical basis for the probability values is crucial. Otherwise, you're likely to simply make up such worthless numbers, influenced only by your preconceived notions. In my argument, none of the numbers I used are something I just made up. They each have empirical backing.

The two important numbers are the prior odds for the resurrection, and the Bayes factor for a human testimony. I set the prior odds at 1e-11: this is, as I said, far more conservative than any requirement of empiricism. There is no way to argue that it should be set lower, although that won't stop some people from abandoning empiricism as soon as it conflicts with their preconceived notions. We'll deal with such arguments in due time.

As for the Bayes factor of the relevant kind of human testimony, I've set it at 1e8. I've given some empirical evidence that this is the correct value, and will provide much more in the chapters to come. But before we get to that, let me acknowledge that this number may be difficult to accept or understand. Many people are more comfortable with probabilities. Bayes factors are a less intuitive, less familiar concept. This is unfortunate, as Bayes factors are crucial to understanding and evaluating evidence. In fact, the logarithm of the Bayes factor is an excellent mathematical translation of what we mean by "the amount of evidence".

There are two ways compute a Bayes factor. The first is from its definition: the ratio of the likelihoods, where the likelihood for a hypothesis is the probability of it generating the evidence in question. In this way, the hypotheses are judged relative to one another, by how well they explain the evidence.

The second way is to compute the Bayes factor from what it does: it moves the odds for the hypothesis. Remember Bayes' rule: posterior odds is prior odds times the Bayes factor. So, if you would change your mind dramatically upon learning of a new piece of evidence, that piece of evidence should have an enormous Bayes factor. The odds of a random person having won the lottery jackpot is very low, but the odds among those who seriously claimed to have won is very much higher. Therefore, that claim of having won the lottery must be accorded a very high Bayes factor.

We can use either method to calculate the Bayes factor, and we will use both in the future to verify our calculations. But before we do so, we should address any niggling doubts you may still have about quantifying human testimony in this way. Maybe these doubts are not exactly about Bayes rule or the value of the Bayes factor, but about some other surrounding issues on which you feel a cloud of uncertainty. You may feel, for example, that 1e8 still somehow gives too much credit to human honesty. Or that 1e8 is too much at odds with the Bayes factor of 1e120 for a chess game record. Since both are a form of human testimony, you may worry that such a large difference points to a flaw somewhere. Or perhaps you're disturbed by how much the Bayes factor for a testimony seems to be influenced by the prior probability of it being true. Or maybe, you're not sure how to stack multiple testimonies together. The math is easiest if the testimonies are independent - you just multiply the Bayes factors - but of course, this almost never happens in reality. So how do we take all these into account?

Answering these questions involves digging deeper into what makes up a human testimony - which we will now do.

The first step in a testimony: the inception of the idea

I'm thinking of a false statement right now. Can you guess what it is?

You almost certainly cannot. There are so many possible false statements out there - a functionally infinite number - that to be able to guess the specific one that I'm thinking of is basically impossible. For instance, the false statement could have been "I played this specific game of chess last night", accompanied by a random chess game record. The odds against guessing that are at the best 1e-120. There was essentially no way for that specific statement to get into your head.

This illustrates an important point in evaluating a claim from human testimony. The thought for a claim, whether it's a truth or a lie, first has to somehow get into the human's head. Then afterwards, they may choose to make the claim or not. Each of these two steps are conditioned on whether the claim is true or false, and the overall Bayes factor for the claim will depend the combination of both steps.

Let's go through a specific example, again of a chess game. Say that you watch a game and record it, and present the following as the game record:

1. e4 e5 2. f4 exf4 3. Bc4 Qh4+ 4. Kf1 b5 5. Bxb5 Nf6 6. Nf3 Qh6 7. d3 Nh5 8. Nh4 Qg5 9. Nf5 c6 10. g4 Nf6 11. Rg1 cxb5 12. h4 Qg6 13. h5 Qg5 14. Qf3 Ng8 15. Bxf4 Qf6 16. Nc3 Bc5 17. Nd5 Qxb2 18. Bd6 Bxg1 19. e5 Qxa1+ 20. Ke2 1-0

Now, if this record is in fact the truth, then how did it get into your head? Well, that's easy - it's the truth, you watched it happen, and you recorded it as it was happening. The probability this game record entering your head, if it really did happen this way, is near certainty.

But what if the game did not in fact happen this way? Well then - it's something of a mystery how you even thought to record this other, incorrect game. Why this specific game record, out of more than 1e120 possible untruthful chess games? The chance of this specific game record even entering into your head in the first place is at most 1e-120, if it were chosen at random.

Then the Bayes factor for the truthfulness of this game record is at least the ratio of the two numbers above - "near certainty" at 1, and 1e-120 - resulting in 1e120. This is just based on the fact that the record even entered into your mind at at all, and before you make any actual claims about whether the record is in fact true. It happens simply as a matter of the regular operation of a human brain, and quite independently of how honest you are.

The "human honesty" step, and dependence factors in multiple testimonies

The next step in the process, after the game has first come into your mind, is to make the actual claim based on what's in your head. Because people are usually honest, you are more likely to make the claim if it's the actual truth, and less likely to make the claim if it's false. This adds an additional Bayes factor for the truthfulness of the game record, but this factor is generally small - much smaller than 1e120. The exact value varies by individuals and circumstances, but something like 1e2 may serve as a guess here. In other words, people tell the truth about 99% of the time (as a guess), when the truth and the falsehoods are both present in their minds.

This explains why some may feel that numbers like 1e8 or 1e120 are somehow too large to be the Bayes factors for a human testimony. They're intrinsically thinking of something like 1e2 as the proper Bayes factor, for a scenario where someone has both a truth and a lie as fully present alternatives in their minds. This may be the proper number if someone merely gave a reply under direct questioning - as in "did you, or did you not, see the defendant at the scene of the crime?" This is the proper Bayes factor if someone flips a coin and tells you that it landed heads. It's the kind of number that intuitively comes to mind when you're asked to assess "human honestly". But it is incorrect for the kind of voluntary, declarative claims made by the earliest Christians announcing Jesus's resurrection.

This also illustrates the effect of dependency factors in how multiple testimonies stack together. The first testimony, presenting new information, should be given a large Bayes factor like 1e8. A second testimony should be given something much smaller, like 1e2, if it only assents to the correctness of the first testimony. Further testimonies offering only confirmations would get ever smaller Bayes factors, but a new, independent testimony would get the full value again.

The "stretchiness" of human testimony

Now, let's throw a twist into the example. Your game record above turns out to be identical to that of the Immortal Game - arguably the most famous chess game in history. What are we to make of that? How does it change the Bayes factor for that game record?

It drastically reduces it, of course. Recall that the enormous Bayes factor exceeding 1e120 came mostly from the first step, where we assumed that a specific incorrect game record had less than a 1e-120 chance of randomly getting into your head. Well, as a very famous chess game, the Immortal Game would not have been selected randomly. Even if that wasn't the actual game that was played, it could have entered into your head in a number of different ways, all of which are much more plausible than 1e-120. This precipitously drops the Bayes factor. So, there's essentially no chance that your game record is correct, right?

Actually, this has far less impact on the final, posterior odds than you might guess. One may think, "Oh, so you're saying that a random chess game someone played just happened to be the exact replication of the most famous chess game ever? Give me a break!" But this was unlikely to be a random chess game, from the beginning. As one of the most famous games ever, the Immortal Game has a much, much higher chance of being played than a random, 1 out of 1e120 game. The game you witnessed may have been an exhibition match from a series of famous historical matches. Or you may have simply gone to an online chess site which replays famous games. Or the two players may have planned out the game beforehand as a demonstration, stunt, or a joke.

So, the Bayes factor of your game record becomes much smaller than 1e120, but the prior odds of that game actually being played becomes much greater than 1e-120. In fact, the two effects will cancel out to a significant degree. A moment's reflection reveals why: the same mechanism is responsible for both effects. A famous game is more likely to be replicated in actual play than a random game. This increases the prior odds. It's also more likely to falsely enter into your mind than a random game. This decreases the Bayes factor. But these two effects have the same origin, and their magnitudes are therefore comparable. The degree to which a game is likely to be replicated is also the degree to which it may falsely enter into your mind. The net effect is that the final, posterior odds of the game being truthfully recorded doesn't change as much as you'd think. If you handed me the above game record and claimed that it was an actual, recent game between two people, I may lean towards believing it was real. I may say "huh, it looks like these guys replicated the Immortal Game in their match", rather than "You're lying. You expect me to believe that their random play just happened to exactly replicate the Immortal Game?"

This explains the large swings in the Bayes factor of a human testimony depending on the circumstances, and why it depends so much on the prior odds of the event in question. If the event is intrinsically unlikely, it has low prior odds, but it's also unlikely to enter into your head in the first place, so the Bayes factor correspondingly increases. Conversely, if the event is intrinsically more likely, the Bayes factor decreases.

So human testimony has this somewhat strange property, in that it may "stretch" to cover a great range of priors, even down to numbers like 1e-120. In this way, human testimony is especially efficient at covering low priors. The less likely the prior, the more the Bayes factor of the testimony stretches, so that the final, posterior odds is not as affected as you'd think.

The maximally unlikely, worst case scenario: when the testimony can't stretch more

Now given all this, what kind of claim would be the least likely to be true? You can't just have low prior odds - that only causes the Bayes factor to "stretch" as detailed above. To get around this, we need to consider a claim that's not merely unlikely, but also interesting or remarkable to the human mind in some way. We thus limit the "stretching" of the testimony about the claim, because there is now a special, alternative way for the claimed event to enter your mind. We still want to have low prior odds for the claim, of course: the goal is to maximize the difference between the prior odds, and the likelihood of the idea entering your head.

So the claimed event should be intrinsically very unlikely, but also "special" in some way. In the chess game example, we achieve this by claiming that completely random play by both players resulted in the replication of the Immortal Game. A particular random game is unlikely, and playing the Immortal Game is special. Similarly, one can claim to have won the jackpot in the lottery. A particular set of numbers is unlikely, and winning the jackpot is special. This is how we get minimal posterior odds. This is how we achieve maximum skepticism.

In such examples, as the priors for the claims become increasingly unlikely, the Bayes factor initially stretches commensurately, and the posterior odds remain steady. But then we reach the "stretching limit" of the claimant's testimony, and the posterior decreases quite suddenly. For a lottery, as the claimed winning amount increase from ten dollars to ten thousand to ten million to ten billion, your respective reactions start off like "okay" ($10) and "nice" ($10K), then "I don't know if I believe you" ($10M) - at which you've reach the limit - to suddenly saying "impossible - no way" ($10B).

Here are some more examples of maximally unlikely claims, where you would have maximal cause for skepticism: You can claim that each member of your family shares birthdays with each respective member of your friend's family. A particular set of birthdays is unlikely, and the matching condition is special. You can claim to have been struck by lighting multiple times. Lightning strikes on humans are rare, and personally experiencing such danger is special. You can claim to have been dealt multiple pocket aces in poker. A particular set of hands is rare, and getting the best hand multiple times is special.

You'll recognize the above examples as the ones we studied earlier, from which we obtained the value of 1e8 as the Bayes factor of a human testimony. In other words, that 1e8 value was calculated precisely for these maximally unlikely scenarios, where someone makes an extraordinary claim about an unlikely but special event. It is under these conditions that the resurrection was found to be highly likely.

The maximally unlikely scenario: an example

Again, note the procedure used in calculating our Bayes factor of 1e8: we consider a special claim, then make it more and more outlandish until you can no longer consider it likely. We then measure the Bayes factor at that point. This is why we considered incrementally increasing numbers of shared birthdays and lightning strikes. This is how we get the Bayes Factor that applies to the maximally unlikely scenarios.

Let us walk through the "shared birthdays" problem as an example. Many numbers below are just guesses, but it's the concepts here that are important. We will have plenty of additional examples later with empirically sourced numbers.

Say you write down the list of birthdays for everyone in your family, and your friend happens to come across it. He then earnestly claims that you share the same birthday with him. Now, is this the scenario we want? No: it isn't the maximally unlikely scenario. We have not yet reached the "stretching limit" of the Bayes factor. The prior is still quite large - you have about a 3e-3 chance of sharing your birthday with your friend a priori.

Now, you might think to apply our previously calculated Bayes factor of 1e8 to our friend's claim. If you do so, then we get a posterior odds of about 3e5 - meaning, the claim of shared birthdays would be virtually always true. This is an absurd conclusion.

What went wrong? Well, our Bayes factor of 1e8 was not calculated for this scenario, and it's too large to be used here. The true Bayes factor in this scenario is probably something like 3e3, giving a posterior odd of about 1e1 - about a 90% chance of you two actually sharing birthdays.

Oh no! So the true Bayes factor is only 3e3? Isn't that much smaller than 1e8? Doesn't that ruin the case for Jesus's resurrection? Not at all, because you can't mix and match the priors and Bayes factors from the different scenarios like that. Remember, the prior in this "shared birthdays" scenario is more than 8 orders of magnitude larger compared to the resurrection: 3e-3 versus 1e-11. If you want to use this scenario and its Bayes factor of 3e3, you must also use the prior odds of 3e-3.

Of course, the net effect of doing so is that after applying a single testimony, the posterior odds here is GREATER than they are for the resurrection. In effect, if someone were to argue for using 3e3 as the appropriate Bayes factor for Jesus's resurrection, they'd essentially be arguing that the resurrection was initially quite likely, and so the final result would be even more favorable towards the resurrection.

What if you and your friend's families shared two, three, or four pairs of birthdays? The patterns that we already mentioned applies, with the initial "stretching" of the Bayes factor and the posterior suddenly dropping off after the "stretching limit" is reached. All these scenarios are summarized in the following table:

There are several important things to note:

As we said, human testimony is "stretchy". The Bayes factor will initially stretch to cover increasingly smaller priors, as we make the scenarios incrementally less likely. So the posterior odds are not much affected. In this way, human testimonies are exceptionally good at covering low priors.

This means that the Bayes factor for a human testimony can be smaller than 1e8, but generally only in cases when the prior is large enough to more than make up for it. So trying to argue against a human testimony by assigning it a small Bayes factor in this way is counterproductive.

The "stretching" could continue almost indefinitely - up to Bayes factors like 1e120 and more - if not for the fact that our claim is "special" - It has an alternate way into the human mind because it's interesting or remarkable in some way. This limits the stretching at some point. The "4 pairs" scenario in the above table illustrates this, where the Bayes factor has reached this limit and the posterior odds drop off quickly.

The appropriate, maximally unlikely claims that best correspond to Jesus's resurrection are those "special" claims, which additionally have a tiny prior and therefore a huge Bayes factor. With such claims, where the Bayes factor has been stretched to its limits, we know that its value must be at least as large as any of the earlier, pre-stretch-limited Bayes factors.

Therefore, in such a claim, any Bayes factors we calculate for any specific, empirical example is going to be an UNDERESTIMATE for the testimonies concerning Jesus's resurrection. This lower bound for the maximally skeptical case is what we earlier calculated to be about 1e8.

So there is no escaping that value: the relevant Bayes factor is really about 1e8, and it's fully applicable to the testimonies concerning Jesus's resurrection.

Pulling it all together: the resurrection story revisited

We now have all necessary components to understand a scenario involving multiple pieces of evidence.

Let's say that someone testifies to a rather unlikely event - say, Peter testifies that "Christ is risen". That testimony has a Bayes factor of 1e8, against a prior of 1e-11. That brings the posterior odds to 1e-3. You should not yet assent to Peter's claim.

So, being skeptical, you turn to John, who is Peter's friend and compatriot. You ask him, "hey, is Peter telling the truth?" and he answers "yes". Now, because John's testimony here is not independent of Peter's, it should not get the full Bayes factor of 1e8. Something like 1e2 is more appropriate. That brings the posterior to 1e-1 - still not quite enough for you to assent to the resurrection.

But while you're considering Peter and John's testimonies, Paul - nearly the last person you'd expect to agree with the other two - randomly bursts into the room and says, "Hey guys! Christ is risen!" What is the Bayes factor for that testimony? Because of the large degree of independence, Paul's testimony should get a large portion of the full 1e8 - easily overpowering the remaining 1e-1 odds, and fully shifting the posterior odds to be much greater than 1.

Paul's testimony, with full dependence factor

Do you doubt that Paul's testimony is enough? Then consider the following: Taking the full dependence factor into account, the Bayes' factor of Paul's testimony is, by definition, given by the following:

P(Paul|John, Peter, Resurrection) / P(Paul|John, Peter, ~Resurrection)

Where "Paul", "John", and "Peter" stand for each of their respective testimonies, and "Resurrection" or "~Resurrection" is our hypothesis in question, whether the resurrection happened or not.

Now, as ever, let us approach this empirically. P(Paul|John, Peter, Resurrection) is not all that unlikely. This is the probability of an opponent of Christianity giving a miraculous conversion testimony. Even apart from Apostle Paul himself, stories like this are old hat. You can't be a Christian for very long without tripping across a load of them.

Then what about P(Paul|John, Peter, ~Resurrection)? This is like the probability of a Paul-like miraculous conversion to your opponent's religion, DESPITE the fact that the religion is false. To get at this number, we only need to pick a religion that both you and I agree is false. Islam or Hinduism will do nicely, as they're mutually exclusive world religions: everyone can pick at least one of those as their "false" example. So, how many Paul-like miraculous conversion stories are there to that religion?

I have not heard of a single case. But it's not just me - I don't think even GOOGLE has heard of a single case. Google search will return different results for different people at different places and time, but my experiences on this front are still telling.

When I searched for "conversion stories to Islam", I got many cases of exactly what I searched for - conversion stories to Islam. So it's not as if Google has some anti-Muslim or pro-western agenda which prevents them from showing Islam-positive search results, nor is there a shortage of conversion stories to Islam on the internet. This is not surprising - the internet is a big place and Google is good at what it does.

But, when I searched for "miraculous conversion stories to Islam", the majority of the results, including the top result, was for Muslims converting TO CHRISTIANITY. And of the few results which actually described conversions to Islam, I could not find one which actually claimed to be miraculous in nature. Most of them are only of the "Islam made sense after I studied it" type. And none of them involved anyone who was as rabidly anti-Islam as Paul was anti-Christian.

Do you understand how remarkable this is? Even Google couldn't find me a single example of a miraculous, Paul-like conversion story to Islam, and when asked to do so it actually returned mostly conversion stories FROM Islam TO Christianity, despite "Christianity" not being in the query at all. That should give you an idea for the relative prevalence of such stories. It's reflective of the absolute dominance that P(Paul|John, Peter, Resurrection) has over P(Paul|John, Peter, ~Resurrection).

In fact, from this experiment, we can see that the magnitude of this dominance - that is, the Bayes factor of Paul's testimony - is in the same ballpark as the Bayes factor of a Google search itself, which is worth many orders of magnitude. It easily and greatly outpaces the numbers like 1e1.

Searching for "miraculous conversion stories to Hinduism" gave me mostly similar results. Nearly the entire first page is about Hindus converting to Christianity.

So, here is the challenge: do you believe that Paul's testimony is not enough? That it can't cover the remaining 1e-1 odds? Then you need to be able to back that up empirically. You need to give me one instance of a miraculous conversion to Hinduism or Islam by a former opponent, for every 10 instances of a miraculous conversion to Christianity that I could cite. Good luck with that, given that even explicit Google searches for such conversion stories return far more cases supporting the Christian position.

Back to the resurrection story

So, after hearing Paul's testimony, and given its large degree of independence, you assign it a Bayes factor fairly close to the full 1e8 value. This easily overcomes the remaining prior, and pushes the posterior odds firmly to favor the resurrection. You should now firmly believe that Jesus did rise from the dead.

And as if that wasn't enough, you then encounter a flood of people all claiming that Jesus rose from the dead - the remaining members of the twelve apostles and other disciples, James, and a crowd of more than 500 people, just to name the remaining witnesses in 1 Corinthians 15. After considering all of their testimony, their claim is now beyond the shadow of any doubt: Jesus Christ almost certainly rose from the dead.

Human testimonies stretch to cover the rest of the Bible

Ah - but what about the other miracles in Christianity? Sure, the resurrection might be well-attested, but what about the numerous other miracles in the Bible which has barely any evidence behind it? For example, only Matthew mentions the resurrection of other people at the time of Jesus's death. He only mentions it briefly, in passing. Many of the remarkable miracles during the Exodus are also mentioned only in that book. The Bayes factor of a single testimony can't possibly cover all of these other stories. How could a Christian believe in such things, if such evidence is inadequate according to our methodology?

So, what have we achieved in this deeper dive into human testimonies?

We've seen that, while there is in fact high variability in the strength of a human testimony, our value of 1e8 for their Bayes factor was already calculated for the maximally pro-skeptical scenario - where the most remarkable, noteworthy claim is being made about a highly unlikely event. This was most fitting scenario for the resurrection testimonies, which gave the lowest posterior odds. And yet, even under these conditions the resurrection proved to be overwhelmingly likely.

Along the way, we've explained why this 1e8 might mistakenly feel too large, when you ignore the priors that the human testimonies have to overcome. For instance, a human testimony can have a smaller Bayes factor like 1e2 - if it's about an event which is already quite probable, like a coin flip or a yes/no question. Conversely, since the resurrection is a highly improbable event, testimonies concerning it should be given a higher value than in our other examples.

This relates to how human testimonies may "stretch" to cover smaller priors. If there is no special way for a particular falsehood to enter into your mind, this stretching can extend to absolutely minuscule priors (as in the record of a chess game). Incidentally, this gave us a nice bonus, in that it justifies our belief in the other miracles in the Bible aside from the resurrection. Yes, these miracles have low priors on their own. But once we accept Jesus, the testimonies about them can easily "stretch" to cover their priors, as such miracles cease to be the most remarkable, special thing that can happen in a world where Jesus rose from the dead.

Putting all this together, we repeated our earlier calculation for the odds of the resurrection, this time taking the dependence factors fully into account. We saw that the strength of just Peter and Paul's testimonies, even with full dependence factors, was easily enough to put the odds firmly in the "likely" side. The rest of the testimonies in 1 Corinthians 15 then puts the resurrection beyond any reasonable doubt.

So, we now have a good idea of how human testimonies comes together. We understand its anatomy and its behavior. And this deeper dive into human testimonies made sense of our intuitions, verified our earlier thinking, and validated our previous conclusion.

Double checking the Bayes factor of a human testimony

Everything above points to 1e8 as the appropriate Bayes factor for the kind of testimonies given for Jesus's resurrection. But for some time now, I've been promising additional examples that would provide more empirical backing for this number. Let us get to those now.

The reporting of experimental results

Some people simply cites "science" against anything outside their narrow, naturalistic worldview. But have you wondered how science actually gets done in the real world?

In a typical hypothesis-testing scenario, a Bayes factor of 1e1 is considered a decent amount of evidence, and 1e2 is considered very strong. Conversely, negative logarithmic values are considered evidence against the hypothesis. Depending on the the specific field of science, the results can often be far stronger than these typical values.

Now, we know that human testimony must be much more powerful still than the reports containing such results. Otherwise, how could you trust these reports? If the human had larger uncertainties than the results, a human report of such results would be worthless. The fact that you generally believe such reports means that you already believe that the human testimony is much stronger.

Of course, not every experimental report can be trusted. They should be replicated whenever possible, and they can be sometimes overturned. But no scientist ever replicates every experiment. They instead generally trust the testimony of others. To require otherwise would make it impossible to do science. This is how the vast majority of a scientist's expertise is built up, and it indicates that the Bayes factor of a human testimony is vastly greater than 1e1 or 1e2.

The frequency of lies

How often have you been lied to? This is perhaps the go-to questions for people who disbelieve the 1e8 value. In doing so they tend to make a set of common mistakes.

Some may say, "people lie way more than 1 out of a hundred million (1e8) times! There's no way that human honesty has odds of 1e8!" But this makes the mistake of confusing a Bayes factor with the posterior odds. They're also forgetting that the bulk of the Bayes factor comes from the idea entering your head in the first place, and is quite independent of human honesty.

One calculation starts like this: let's say that people have about 10 opportunities to nontrivially lie to you in a given day. Multiplying by about 300 days a year and assuming that you're about 30 years of age, this amounts to about 100,000 (1e5) opportunities in your life for someone to tell you a nontrivial lie.

At this point, many make the mistake of dividing 1e5 by 1e8, and conclude that a Bayes' factor of 1e8 would imply a 1e-3 odds of you having been lied to in your lifetime - an obviously absurd conclusion. This mistake comes from confusing the Bayes factor with the posterior odds.

The correct math here requires getting the prior and posterior odds, and getting the ratio between them. In essence, we're using the second of the two ways to calculate a Bayes factor: to measure it by how much it moves the odds, from the prior to the posterior.

So, how often have you been nontrivially lied to, in your 30 years of life? Let's say 1,000 (1e3) times. That corresponds to roughly 3 nontrivial lies per month. That means that the posterior odds of a lie is 1e3 out of 1e5 opportunities, or 1e-2. The posterior odds of a truth-telling is therefore 1e2. That is, people generally turn out to have lied about 1% of the time.

But what are the prior odds? Remember, we're specifically interested in someone making a positive assertion about something that happened - such as "I got into a car accident", "I went to Harvard", or "I was vacationing in France that day". In such cases, the priors are quite small. Most specific events are improbable. Let us generously assign 1e-3 as the prior odds of the statement being true.

Then, the Bayes factor is the factor which turns that 1e-3 to the posterior odds of 1e2. In this case, it's 1e5, because 1e-3 * 1e5 = 1e2.

Here, people often make another mistake: they say, "aha! 1e5 is still smaller than 1e8!" But they're forgetting that a prior odds of 1e-3 is still nowhere enough to stretch the Bayes factor to its limit. Remember, human testimony is exceptionally good at overcoming low priors. Compared to the typical lies mentioned above, the claims we're discussing involve events like winning the lottery, being struck by lightning, or someone rising from the dead. Such events will have far smaller priors, and therefore far larger Bayes factors. As I mentioned before: this is why any specific Bayes factors we calculate for any empirical example is going to be an UNDERESTIMATE for the testimonies concerning Jesus's resurrection. The larger the prior odds are in the example, the more of an underestimate the calculated Bayes factor will be.

In addition, the kind testimonies involved in Jesus's resurrection are not trite, everyday lies. We're specifically concerned about sincere, insistent, enduring, and life-changing personal testimonies. This set of conditions easily adds a couple of orders of magnitude to the Bayes factor.