Interpreting the Genesis creation story

I had originally written this as a long series of separate posts in 2014.

That work has become much more relevant recently, with the publication of S. Joshua Swamidass's new book, "The Genealogical Adam and Eve: The Surprising Science of Universal Ancestry". The book covers much of the same topics as my series, and I highly recommend it. Joshua and I arrived at our conclusions independently, but we have become aware of one another since then, and he has endorsed my work.

Jon Garvey has also published a book on this topic: "The Generations of Heaven and Earth: Adam, the Ancient World, and Biblical Theology". This approaches the idea of the Genealogical Adam and Eve from a theological angle, which complements Joshua's scientific approach in his book. Jon and I also came to our ideas independently, I also highly recommend his book, and he, too, has endorsed my original work.

So we (and many others) all independently arrived at this new interpretation of the Genesis creation story - which I believe to be absolutely groundbreaking. It compromises nothing, either on the inerrancy of the Scriptures, or on the data on evolution. It harmonizes all the relevant scientific, historical, and biblical facts. In fact, I now consider the whole creation/evolution debate to be a "solved problem" at the highest levels.

In light of all this and the expected interest that it will generate, I've decided to revisit my original series. I've consolidated them all into this one post here, and updated it to represent the new things I've learned though Joshua, Jon, and others.

Table of contents

- Interpreting the Genesis creation story: an introduction

- Interpreting Genesis 1 by looking through John 1

- How is "light" used in the Bible, particularly in the creation story?

- The simple essential meaning of the Genesis creation story

- Adam and Eve were historical persons. Who were they?

- The relational propagation of the image of God

- An aside on the image of God

- The worldwide propagation of the descendants of Adam and Eve

- Interpreting other Bible passages (Part 1: Cain and Abel, Seth and Enosh)

- Interpreting other Bible passages (Part 2: Nephilim, Noah, etc.)

- Common arguments about the creation account

- The biblical timeline of the universe

Interpreting the Genesis creation story: an introduction

First, we need to lay down some foundations. I've written several posts on how we should interpret the Bible. I have said that:

The Bible, like scientific data, is sacred and infallible. We approach it accordingly.

This leads us to certain well-established principles of Bible interpretation.

Furthermore, the Bible should be interpreted using science when appropriate.

I have also written on the proper role of science and its relationship to Christianity. I have said that:

Therefore, Christianity provides the firm foundation for doing science, and science in turn reveals to us a great deal of about God.

Furthermore, science taken as a whole provides overwhelming evidence for God.

With these as the foundations, I can finally begin this work on the Genesis creation story. Here are the key points in my interpretation:

The seven-day creation week in Genesis 1:1 - 2:3 is not meant to be taken literally. It's a prologue: it serves as an abstract, symbolic, and non-chronological introduction to the rest of Genesis, and the whole Bible. Its primary purpose is to inform us that God created everything to be "very good", and that we are made in his image.

Starting from Genesis 2:4, where the "second creation story" starts, the stories are pretty much "literal". From this point on in Genesis, there is a continuity of narrative all the way to the end of the book. Genesis 2-11 should therefore be interpreted the same way we interpret any of the stories about the patriarchs, in a very "literal", down to earth, matter-of-fact sense.

This means that Adam and Eve were historical persons who lived several thousand years ago. They are ancestors to all humans alive today, although they were not the only humans living in their time, or the first members of the biological species. By virtue of being their descendants, we also bear the image of God, and share in their original sin.

Noah's flood was a local flood.

On the science side of things, I hold to the standard Big Bang cosmology and the theory of evolution, which says that the Earth and the universe are billions of years old. Standard scientific stuff. I believe that mainstream science is basically correct on these matters. My position here may be characterized as theistic evolution, although my interpretation is much more specific on certain points.

"But wait", you say. "How could you believe in a historical Adam and Eve, and also in modern science? Anatomically modern humans appeared some 300,000 years ago, yet you say that Adam and Eve lived only several thousand years ago?" That's right. It turns out that you don't need to be the first member of a species in order to be an ancestor to all the current members of that species. This is an important point, which will be more fully explained in the appropriate sections.

These ideas represent my best attempt at interpreting the Genesis story. I believe them to be correct, free from flaws, and compatible with all biblical and scientific data. They are not yet completely set in stone. But I have a great deal of evidence for my interpretation, and for me to wholly reject it would require counter-evidence on a scale that is unrealistic to expect. Since I initially proposed these ideas, I have only grown more certain of its correctness, as they have grown in evidence in the form of significant external validations and more recent research.

In fact, although I had argued earlier that we should use science in interpreting the Bible, I believe that my interpretation can stand simply on its strong scriptural support alone. Therefore, over the course of this work, I will avoid mentioning science when the main topic at hand is to interpret the Bible. Of course, if you do consider science in addition, my interpretation becomes more certain still.

At this point I would like to reiterate that we, as Christians, can disagree on this topic while still being loving, and that living out the Gospel is more important than being right. I have a number of people who disagree with me on this issue, whom I deeply respect. And I don't mean that flippantly: these are people in my personal life whose knowledge of the Bible exceeds my own in many areas, whose walk with Christ are deeper than mine, whose actions I would consider to be a better witness, and whose life I would like to live. Yes, we disagree on this important issue of interpreting the Genesis creation story, but that doesn't prevent us from loving and being in fellowship with one another through Christ.

I will further explain and defend each point of my interpretation in the remainder of this work. Here is the summary of the contents in the sections to come:

Interpreting the Genesis creation story: an introduction: This section. Here I lay out some prerequisites for Bible interpretation, and summarize the whole work.

Interpreting Genesis 1 by looking through John 1: John 1 is the best biblical tool we have for interpreting the Genesis creation story. In this light, we see that the seven days of Genesis 1 are a poetic prologue to the rest of the Bible, written using an abstract, symbolic, "big picture" style - which is exactly how the Gospel of John also starts.

How is "light" used in the Bible, particularly in the creation story?: This is a case study in how the Bible uses the word "light". We examine every verse that mentions "light", and find that the Bible uses that word figuratively much more often than it uses it literally. The often made claim that we should prioritize literal interpretations over figurative ones is shown to be wrong.

The simple essential meaning of the Genesis creation story: In the midst of discussing the controversial details, we must not forget that the creation story has a simple, important message, as the first passage of the Bible: God is the creator of the universe. He created all things to be good. He made us in his image to rule over the rest of creation. Although we then sinned and fell, God still cares for us and interacts with us. The rest of the Bible is the story of that interaction.

Adam and Eve were historical persons. Who were they?: Adam and Eve are ancestors to all humans alive today and the first fully human beings. But they were not the first biological humans, or the only humans around in their time. Instead, they were recent common ancestors for all of us living today. Because they are our spiritual ancestors, we, too, are made in the image of God, but we're also affected by their original sin.

The relational propagation of the image of God: The idea that Adam and Eve are recent common ancestors works very well in fitting all the data, but it also raises some questions. In particular, it implies that there were non-Adamic biological humans who were not made in the full image of God. I explore and resolve this issue by making one major modification to my model, by expanding the method of propagation for the "image of God" beyond just biological means.

An aside on the image of God: We take a short detour to explore the idea of the "image of God" and its broader implications. In particular, I develop a general principle for how to treat any entity which may bear the image of God to any extent. This principle can then be applied to numerous classes of beings, including the non-Adamic humans.

The worldwide propagation of the descendants of Adam and Eve: I consider how the descendants of Adam and Eve could have spread throughout the Earth, addressing issues such as whether they could have spread quickly enough, or how they could have gotten to the Americas, or reached isolated peoples. I then evaluate the overall certainty of my model, and address how it might change in the future.

Interpreting other Bible passages (Part 1: Cain and Abel, Seth and Enosh): How does this model explain the other tricky passages in the Bible? Here I look at several story elements in Genesis 4. Who was Cain afraid of? Who was his wife? Why did he build a city? What does it mean that people "began to call upon the name of the Lord"? My interpretation deftly handles all these questions, while they are often troublesome for its rivals.

Interpreting other Bible passages (Part 2: Nephilim, Noah, etc.): I continue exploring the fit between my model and the other passages in the Bible, such as the story of the Nephilim, Noah's flood, the Tower of Babel, and the theologically important verses in the New Testament which touches on the creation story.

Common arguments about the creation account: I consider some often-heard arguments about the Genesis creation account: "the Hebrew word for 'day' is always literal when paired with a number", "other passages say the world was created in six days", and "How could there be a literal day before there was a Sun?". I also consider the "no death before Adam" argument, the problem of incest, and many other issue.

The biblical timeline of the universe: In this conclusion for this work, I lay out the timeline of the major events in the history of the universe, and weave them into the Gospel narrative.

Interpreting Genesis 1 by looking through John 1

Genesis chapter 1 needs no introduction.

But interpreting this immensely important passage has ever been a difficult and controversial endeavor. A standard practice when we run into such difficulty is to look to other parts of the Bible which could clarify our passage: we apply adages such as 'Scripture interprets Scripture', 'New Testament interprets Old Testament', and 'clear passages interpret vague passages'. Ideally, this other passage that aids us in Genesis 1 would be an easy-to-interpret New Testament text that clearly references the Genesis creation story. This ideal passage actually exists: it is John 1.

The parallels between John 1 and Genesis 1 are impossible to miss. They begin with the same words, invoke the same themes (creation, light, life), and as we'll see, employ the same stylistic structure. The authorial intent in John 1 to parallel Genesis 1 is so clear that John 1 should be, by all rights, the primary passage through which we interpret Genesis 1. It is arguably the longest passage outside Genesis itself which talks about the creation event, and is one of the very few passages in the entire Bible which can match the gravitas of Genesis 1. If we believe in the unity of the Scriptures, we must interpret Genesis 1 in light of John 1.

And yet, I have seen virtually no attempts to interpret Genesis 1 this way. I do not know why. This is all the more surprising in light of other verses, such as Exodus 20:11, which I have seen applied to interpret Genesis 1. Compared to Exodus 20:11, John 1 is longer, addresses the topic of creation more directly, and parallels the style and structure of Genesis 1 more closely, yet in my experience, it is referenced less often.

So, what features of John 1 are particularly relevant to Genesis 1?

First, note that John 1 begins with a series of highly abstract, symbolic statements. They are fortunately easy to interpret, since we know that they all refer to Jesus. None of the statements in the first part of this chapter are to be taken literally. John 1 begins: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God". Here we understand that there weren't a bunch of letters somehow floating around God. Even interpreting "Word" as "reason" or "logic" falls short of the true meaning which can only be accessed symbolically. The same goes with verse 4 and 5: "In him was life, and the life was the light of all men. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it". Christ is not literally light (he is not a bunch of photons) or literally life (he is not the abstract concept of "life"), but these are things that represent him.

John 1 continues in this abstract, symbolic fashion for the first 18 verses. It does make some firm statements which could be said to be "literally" true, such as verses 12-13, or verse 6 where it mentions John the Baptist by name. But even these statements are highly conceptual and very general in scope, and the abstract symbolism of the first few verses are thoroughly mixed in with them. Furthermore, John 1 doesn't even mention Jesus by name until verse 17, and even that passage begins with this well-known mix of abstractions, poetic symbolism, and concrete reality: "And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us…"

In fact, the nature of the topic in the first part of John 1 is so abstract, conceptual, and symbolic that the passage cannot be read literally. It would become absurd if you tried. "The Word became flesh" would then mean something like "the letters turned into sausages" in this ridiculous sense. This is a limitation of human language: we do not have a separate way of talking about nonphysical things other than to employ literal language metaphorically. We have no other option if the topic itself is not purely physical, and this metaphorical reading is not automatically inferior to a literal reading simply because it's metaphorical.

After this abstract start, the writing style finally settles down in verse 19, and the down-to-earth narrative begins. The change is actually very abrupt. After 18 verses of highly conceptual words like "the beginning", "Word", "God", "light", "life", "glory", "grace", and "truth", verse 19 says, "And this is the testimony of John, when the Jews sent priests and Levites from Jerusalem to ask him, 'Who are you?'" In a single verse, we have a specific people group (Jews), occupation (priests and Levites), city (Jerusalem), and the start of a simple dialog, which are all to be interpreted literally. After this sudden transition from "abstract" to "concrete", the story continues on in this comparatively mundane, literal fashion for much of the rest of the book.

This sudden change in style, and the corresponding change from an abstract to a concrete topic, strongly suggests that the first 18 verses of John are something like a prologue. This is not surprising - after all, prologues are a common literary tool.

How does this interpretation of John 1 - which is quite certain and noncontroversial - carry over into Genesis 1?

Extremely well. We're using John 1 as a key to unlock Genesis 1, and it turns out to be a perfect fit. John 1:1-18 is the prologue to the gospel story, and it introduces Jesus as God's incarnate Word. Genesis 1:1-2:3 is the prologue to the whole Bible, and it introduces God as the Creator of the world.

Like in John, the Genesis prologue - which consists of the seven days of creation - is abstract and symbolic, and is not meant to be taken literally. Although the symbols are not as obvious as in John 1, two things stand out as pretty clear metaphors: the light that God created on the first day, and God's rest on the seventh day. For how could you ignore the profound meaning that "light" has as a metaphor, and only interpret it as some photons zipping around in space? And what could it even mean that God "literally" rested?

Also like in John, the statements made in this prologue are very broad and non-specific, especially compared to the text that comes right afterwards. Note, for example, that the humans are not named as Adam and Eve in chapter 1: they are only said to be made male and female. No animals, no plants, no places, not even the sun and the moon are specifically named. This, combined with the poetic repetition of many phrases over the days of creation, give the whole story that abstract, conceptual feeling, standing apart from the world we experience, which is concrete, detailed, and mundane.

Contrast that with the passage that immediately follows this prologue - the so-called "second account of creation" that starts on Genesis 2:4. Like in the book of John, there is a dramatic, instantaneous change in the style and the level of specificity. The sweeping, poetic style of the first chapter settles down, and numerous, mundane details are sprinkled into the story. The text mentions specific rivers, trees, and places, and even points out where to find gold and gemstones. Just this change would be good evidence that the creation week should be interpreted differently than the remainder of Genesis. But additionally, consider that the exact same change happens in John, and it becomes very clear that the prologues in Genesis 1 and John 1 are parallel passages that should be interpreted in the same manner - metaphorically.

So it's best to look at Genesis 1:1-2:3 as a kind of prologue. Let's examine some other well-known prologues, to see that Genesis 1:1-2:3 does in fact belong to this class of writing, and to better understand how to interpret it.

"A Tale of Two Cities" opens thus:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way - in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

The book then starts the actual narrative after this prologue, dropping the broad, abstract generalizations and providing many more details. It gets down to the business of establishing the setting and introducing characters and so forth. Also noteworthy is the poetic use of repetition to set itself apart from the rest of the book, alerting the readers that it should be interpreted differently than the text that follows. All of these are features found in the Genesis creation story, and nearly all of them are also found in John 1.

Here is "Romeo and Juliet"'s prologue:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross'd lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents' strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark'd love,

And the continuance of their parents' rage,

Which, but their children's end, nought could remove,

Is now the two hours' traffic of our stage;

The which if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

Again, note the paucity of details, the poetic structure, and the broad, general language. Other than the single mention of "Verona", this story could be set anywhere. Note also that different rules of interpretation apply here: the main script would rarely break the fourth wall this explicitly and acknowledge that this is a play. Of course, after this prologue, the abstract generalizations are dropped, and the details are filled in.

Some may say that the two examples above cannot be compared to Genesis 1, as they belong to very different types of writing. That may be, but prologues are so widely used that they can actually cover over this gap. They were used in ancient Greek literature, which often began by invoking the muses for inspiration. They are still being used today. The work in question doesn't even have to be literature: in Disney's film "Frozen", the song "Frozen Heart" conforms to all the above-mentioned patterns and thus serves as the prologue to the movie. In fact, prologues are not even restricted by the fiction/nonfiction divide: here is the preamble to the Constitution of the United States:

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.

The features here should be familiar by now: the scarcity of details, the broad, sweeping language, the sudden change in style and language structures that sets it apart from the remaining text, and the corresponding need for a different interpretive lens. Lastly, the tendency for prologues to be more poetic than the remaining text is displayed well here - even though the U.S. Constitution is a legal document, the founders could not help but add small literary flourishes to the preamble, such as "a more perfect Union" and "the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity". The same tendency can even be seen in some science textbooks, which occasionally wax poetic in a "prologue" about science, nature, and truth before it actually gets to teaching you specific things.

So, what have we learned by looking at these well-known prologues? Several things: prologues are set apart from the remaining text by a markedly different style and structure. They do not give specific details, but make broad, general statements instead. They are more abstract, metaphorical, and poetic than the remaining text. And lastly, all this requires prologues to be read differently, through a more metaphorical, abstract interpretive lens.

All of this applies to the creation week in Genesis 1:1-2:3, which perfectly conforms to these patterns that are well established by other famous prologues. But most importantly, these same patterns are also found in John 1, which is the most relevant passage in the Bible for interpreting the Genesis creation story. The explicit parallels between these two passages leave no room for ignoring John when we interpret Genesis. The unity of Scripture requires that we interpret them in the same way - and John 1 clearly employs metaphor and symbolism to express highly abstract ideas in a broad, sweeping prologue to the rest of the book.

We therefore conclude that both Genesis and John begin with a prologue. This means that we should not interpret the "days" in the creation week as literal 24-hour periods. Furthermore, we should not attempt to extract specific scientific facts or chronology from the seven days of creation, as prologues intentionally leave out details to make broad, "big picture" statements instead.

What, then, is the actual meaning of Genesis 1, if it's not meant to be read literally? We will come to that question soon enough. But meanwhile, let us hammer home the point of this section, by doing a case study on the use of the word "light", in Genesis 1 and in the rest of the Bible. This will help us to further understand some principles of Biblical interpretation.

How is "light" used in the Bible, particularly in the creation story?

I mentioned that the creation of light on the first day of Genesis 1 is a strong hint for the passage being metaphorical. Light is simply too powerful as a symbol to discount this interpretation. In order to back up my claim, I have examined every single verse that mentions "light" in the Bible, and categorized them according to their usage of that word. It turns out that the Bible uses "light" figuratively far more often than it uses it literally. There are two main results: first, a literal reading is not to be given priority over a figurative one simply because it's literal. Second, while it is not strictly incorrect to interpret the light in Genesis 1 literally, the figurative interpretation is more compelling and more in line with the usage of "light" in the rest of the Scriptures.

This section is written to present these findings. It is fundamentally about how to interpret one word in the opening passage of the Bible. To tackle this question, I went back to our basic principles: the Bible should be interpreted as a whole, and difficult verses should be interpreted in terms of simple verses. The idea is that a comprehensive cataloguing of every mention of "light" in the Bible will yield some insight into how it's used in Genesis 1.

This involved interpreting hundreds of verses. I could not look at each of them in full depth, so I categorized them along just two dimensions. First, I looked at the role that light has in each verse, and categorized it as "central" or "peripheral":

"Central" means that the concept of light is one of the main topics of the verse in question. Light is a crucial element in interpreting the text.

"Peripheral" means that "light" is mentioned in the verse, but it's not the main topic. The text could easily be understood without the reference to light, or with a different word substituted instead. Obviously these verses should be given lesser weight in evaluating how "light" should be understood in the Bible.

Second, I interpreted the verse and categorized how "light" should be understood, labeling it as "literal", "figurative", "both", or "ambiguous".

"Literal" means that "light" in this verse is a physical light that actually exists and actually shines. But, if the verse is in a fictional story such as a parable, I still categorized a physical light in the story as "literal" although it didn't exist in real life.

"Figurative" means that "light" is used to represent something else in this verse, such as perception, truth, awareness, et cetera.

"Both" means that there is a literal light in this verse, but that light also clearly symbolizes something else as well, so both methods of interpretation are applicable.

"Ambiguous" means that I could not determine the sense in which "light" was used in this verse.

This gives eight possible combinations of categories. The following is a list of these eight combinations, and an example of a verse that fits into that combination, provided to help you better understand how I classified the verses.

"Central" and "literal": Exodus 25:37. This is a passage about the construction of the lampstand for the Tabernacle. The function of the lampstand is to give light, and the specific verse is on setting up the lampstand to perform that function. So this is a literal light, and the verse cannot be interpreted apart from this light-providing function of the lamp.

"Peripheral" and "literal": Genesis 44:3. This passage describes Joseph's brothers leaving Egypt "as soon as the morning was light". "Light" here is clearly talking about the literal light that makes the morning bright, but it's not crucial to the story. Even if the verse had simply read "as soon as it was morning", its meaning would hardly change.

"Central" and "figurative": Matthew 5:14. This is the 'salt and light' verse. We are not literally light, but the nature of light - its visibility and its power to illuminate - is the primary topic of discussion, so "light" plays a central role in this verse.

"Peripheral" and "figurative": Psalms 56:13. In this verse David is giving thanks to God for saving his life. The phrase he uses - "light of life" - is clearly figurative, and he could have instead used "gift of life", "blessing of life", "breath of life" or any other metaphor without changing his meaning. He also could have simply said "life".

"Central" and "both": Acts 22:6. This is Paul recounting his conversion story. The light that shone around him is real and it plays an important role in his story, and he mentions it multiple times. In general, if several references to "light" are clustered together, it's a major clue that it plays a central role in the story. Moreover, light also has clear symbolic meaning here, as the presence of Jesus, as Paul "seeing the light", et cetera.

"Peripheral" and "both": Acts 9:3. This is the same story of Paul's conversion. But the way that Luke tells the story here, the light simply marks the beginning of the story and he doesn't mention it afterwards. He could have simply began with "suddenly Saul fell to the ground and heard a voice say to him", and it would not significantly change our interpretation of the story. This demonstrates that the same event could fall under different categories in different verses, depending on how a particular verse tells the story.

"Central" and "ambiguous": Revelation 8:12. I'm not going to pretend to understand Revelation. But the idea that the light-giving celestial bodies are "struck" involves light in a central role, as this event comprises the entirety of the consequence of the fourth trumpet, which seems important.

"Peripheral" and "ambiguous": Isaiah 13:10. This is about the "day of the Lord", in an "oracle concerning Babylon". I do not know how to interpret it. I have labeled it "peripheral", because although the language is nearly identical to the one used in Revelation 8:12, the wider context around the verse makes it clear that the main point of the passage is that it will be a bad day, so the exact meaning of "light" is not as important.

As you can see, there is some room for subjectivity in some of my interpretations. It is, after all, just my interpretation. There is also room for improvement in the categorization. I do not actually believe that Bible verses, or any expression of language, can be neatly categorized as being "literal" or "figurative". There can be lots of splitting of hairs in the detailed depths of interpretation. However, I do believe that my interpretations are generally correct, and as we'll see my results are sufficiently robust that a few misinterpreted verses won't affect the conclusion.

In order to categorize all these verses, I had to select a particular translation of the Bible. I chose the ESV, as it's a popular translation that's held in high regard by the people I trust, yet I am not personally all that familiar with it. This reduces the possibility of me choosing a translation to affect the outcome of this study, or of my familiarity influencing the interpretation of particular verses.

According to BibleGateway, there are 219 verses in the ESV that contain the word "light". Of these, 11 verses do not apply to our interests. I have labeled these as "n/a". Some of these verses only have "light" appearing in the section headings but not in the actual text of the verse itself. Others use a homonym of "light", used in the sense of weight, or to come upon something - examples of texts like this are "this is a light thing in the sight of the Lord", or "we shall light upon him as the dew falls on the ground". The remaining 208 verses can then be categorized into the eight combinations listed above.

All above-mentioned procedures were decided before I started interpreting any verses, to prevent the possibility of me changing the rules in the middle to suit my own conclusions.

The detailed results, including the individual categorization of all 219 verses, can be found in the spreadsheet linked below:

How "light" is used in the Bible (spreadsheet)

How "light" is used in the Bible (html)

This is the number of verses that fell under each of the eight category combinations:

central + literal: 5

central + figurative: 49

central + both: 10

central + ambiguous: 12

peripheral + literal: 21

peripheral + figurative: 98

peripheral + both: 4

peripheral + ambiguous: 9

In total, "light" is used purely figuratively in 147 out of 208 verses (70.7%), whereas it's used literally ("literal" and "both" categories summed up) in 40 out of 208 verses (19.2%). Even if we count all the ambiguous cases outside Genesis 1 as being literal, that only brings it up to 54 out of 208 verses (26.0%). The Bible, as a whole, uses "light" in a purely figurative sense a large majority of the time.

If we only consider the "central" category, where "light" is a main topic of the verse, "light" is used purely figuratively in 49 out of 76 verses (64.5%), whereas it's used literally ("literal" and "both" categories summed up) in 15 out of 76 verses (19.7%). Even if we count all ambiguous cases outside Genesis 1 as being literal, that only brings it up to 20 out of 76 verses (26.3%). The Bible, as a whole, uses "light" in a purely figurative sense a large majority of the time when it's a main topic in a passage.

So, depending on exactly which numbers you look at, the Bible uses "light" purely figuratively about three times more often than it uses it literally. This difference is so great that a few misinterpretations on my part would not have significantly altered the result. This leads directly to my first conclusion: a literal reading of the Bible is absolutely not to be given priority by default over a figurative reading. This would actually lead to the wrong interpretation in most cases with "light", as we have just seen. The Bible clearly uses "light" figuratively much more often, so if anything we should default to the figurative meaning when we're attempting to interpret an ambiguous verse.

In fact, in the course of interpreting these hundreds of verses, I noticed that this was happening to me automatically. My mind defaulted to the figurative meaning as I read through passage after passage where this was the correct interpretation, whereas the rarer verse where the literal interpretation is correct would give me pause due to its rarity. Furthermore, insofar as one can notice these things, I did not notice my mind first attempting a literal interpretation, then trying the figurative interpretation only after the literal interpretation failed. Instead my mind grasped the correct interpretation from the surrounding context, without trying the two types of interpretation sequentially. This makes sense: as C.S. Lewis said, the limits of human language means that any abstract concept can only be discussed metaphorically. Therefore the correct interpretation of any work of language is not determined by trying for a literal interpretation first, then a figurative interpretation only as a backup. Instead it is determined simply by the topic and the context. This also agrees with the consensus of linguists today, who reject the idea of a sequential approach to language interpretation.

So, literal readings are not intrinsically better than figurative readings. They are not intrinsically more clear or more respectful to the Bible. On the flip side, figurative readings are not intrinsically inferior, nor are they only a fallback position after the literal interpretation has failed, nor should you feel as if you're eroding the authority of the Scriptures in any way if you employ them. Instead, the proper interpretation should be determined by applying the established principles of interpretation, such as context and consistency, without regard to whether the interpretation is literal or figurative. And when these principles are applied to a word of overwhelming metaphorical power like "light", it is more natural and intuitive to try a figurative interpretation first. This point of view is verified by how the Bible itself actually uses "light".

This is a very robust conclusion. Virtually no amount of restricting the general context of the Bible could possibly reverse it. In fact, even if you were to throw out all the data from Psalms on the grounds that Genesis 1 is not poetry (which is debatable), and also throw out all the data from the Gospel of John on the grounds that John clearly had a thing for using "light" figuratively (which is absurd), the above result would still hold. The remaining part of the Bible uses "light" figuratively in 109 out of 168 verses (64.9%). If we further only consider the verses where "light" is a central topic, then it's 33 out of 60 verses (55.0%). In contrast, even by the most generous count ("literal" + "both" +"ambiguous" outside of Genesis 1), the remaining part of the Bible uses "light" literally in only 52 out of 168 verses (31.0%), and in 20 out of 60 verses (33.3%) among the "central" verses (the remaining 7 verses are the ones in Genesis 1). The Bible still uses "light" figuratively much more often than it uses it literally.

The only way to resist this result is to decide beforehand that Genesis 1 is written as a history, and to restrict ourselves to only those verses in the Bible that are part of the historical books. Then the majority of the few remaining verses will refer to "light" literally. But this seems to me to be a clear violation of the sound principles of Bible interpretation.

All this is not a conclusion, of course. It is only a starting point. It shows that you should give a significant amount of due consideration to interpreting "light" in Genesis 1 figuratively. But you do not necessarily have to conclude that this interpretation is correct: again, the correct interpretation will be determined by the topic and the context of Genesis 1.

So what is the specific context for the first chapter of Genesis? And how should we interpret "light" in this passage? My answer is the previous section: The seven days of creation in Genesis are a prologue, which is poetic and highly abstract in nature. Its closest parallel is John 1, which also starts off with a poetic, abstract prologue. And this parallel between these passages is reinforced by our study of "light": outside of Genesis 1, John 1 has the most frequent mentions of "light" in the Bible. They contain 7 and 5 "central" references to "light" respectively - more than any other chapter in the Bible. This is, of course, only expected, as they are meant to be parallel passages, so that the interpretation of John 1 can serve as the key to Genesis 1. If you want to understand "light" in Genesis 1, consider its meaning in John 1: they are likely to have similar interpretations.

But how about an interpretation of Genesis 1 within the context of the book of Genesis? Well, "light" is hardly mentioned in Genesis outside its first chapter. This makes perfect sense if the creation week is a prologue. A prologue would have its own symbols and word choices which would set it apart from the rest of the text, as I mentioned in the previous section.

Alright, how about in the context of the Pentateuch? Here the case for a literal interpretation of "light" in Genesis 1 becomes stronger. In the first five books of the Bible, outside Genesis 1, there is no reference to "light" in a purely figurative sense. Furthermore, there are several references to a literal light serving as a spiritually significant symbol, such as the light from the pillar of flame that led the Israelites out of Egypt, or the light from the golden lampstand in the tabernacle. Something like this, I believe, is our best bet for interpreting "light" in Genesis 1 if we must remain literal: a physical light which has a great deal of spiritual significance. There must at least be some symbolic meaning, as the Bible never spends so much time on literal lights with no figurative meaning.

This "literal light symbolizing something spiritual" would be a decent interpretation, if we were to look only to the Pentateuch for our context. It is for this reason that I don't say that it would be strictly wrong to interpret "light" in Genesis 1 literally - as I previously said, it's a position that I disagree with but still respect. However, on the whole, I don't think that this explanation holds up against the overall frequency with which the Bible uses "light" in a purely figurative sense, or the unbreakable link between Genesis 1 and John 1 and the figurative interpretation that it suggests.

So, upon examining every Bible verse which contains the word "light", we see that the Bible uses the word figuratively most of the time, demonstrating that the figurative use is in fact the norm, and that a literal interpretation is not to be considered automatically better. Furthermore, the references to "light" ties Genesis 1 and John 1 together even more strongly than before, and hints that the seven days of creation are in fact an abstract prologue, like the first 18 verses in John 1. While there is some precedence that the creation of light in the first day could refer to a literal, physical light which also has spiritual, symbolic significance, this requires a very specific context for interpreting "light": looking at only the Pentateuch, instead of the Bible as a whole or Genesis in particular. Overall, there is simply more evidence for interpreting "light" figuratively rather than literally when we look at the whole Bible.

The simple essential meaning of the Genesis creation story

In attempting to understand the Genesis creation story, it's easy to get lost in the many different interpretations and get discouraged. You may begin to wonder, "what hope do we have of understanding the rest of the Bible, if the first chapter is already this confusing?"

On a related note, if you don't hold to a strictly literal interpretation of the creation week, you must answer the following question: "what then is the true meaning, if it's not literal?" Not answering this question is a common pitfall I see in non-literal interpretations. People will spend a lot of time explaining why Genesis 1 cannot be literal, but then make no attempt at explaining it in a different way that draws out the actual meaning.

This then opens the way to the charge that "if you don't interpret Genesis literally, then you'll start allegorizing any passage to say anything you want". This is a fair criticism, if all you do is state that "it's not literal". Having stated what a passage doesn't say, you must also explain what it does say.

All of the above issues could be resolved in a single stroke by providing the simple, noncontroversial, essential meaning of the creation story. Here it is:

The creation story in Genesis 1:1-2:3 tells us that God is the creator of all that exists. He created everything to be good - using order, reason, and patterns in every step of creation. As the pinnacle of his work, he created us - human beings - in his own image, as masters over his excellent creation.

The next few chapters of Genesis tells us that despite all this, we humans sinned by disobeying God. We thus fell away from him, but God did not totally cut us off. Despite our sins, God still cares for us and continues to interact with us. The rest of Genesis, and the Bible, is the story of these interactions between God and humanity.

That's it. These are the facts that everyone who accepts Genesis can agree on. They are simple yet immensely important, befitting the first chapter of the first book of the Bible. They conform to the adage that important doctrines are based on simple interpretations. They are far more important than debates over evolution or the age of the earth, although this is sometimes forgotten in the heat of the controversy.

Given this interpretation, you don't have to get discouraged by the many conflicting viewpoints about the creation story. They are all just tangential footnotes in comparison to this enormous meaning that everyone agrees on. The important things continue to be simply understood.

This also answers the question, "how do you interpret Genesis 1, if you don't interpret it literally?" The above meaning works perfectly well in a figurative interpretation of the Genesis creation story. It also answers the accusation that anything goes in a non-literal interpretation, which is plainly untrue. Consider: when Jesus said "I am the bread of life", he was clearly speaking metaphorically, yet there is a simple, correct interpretation that everyone can agree on - that Jesus is crucial for our spiritual well-being. So "bread of life" cannot be interpreted in whatever way we want, despite it being clearly metaphorical. Why should the passage in Genesis be different? By providing the above simple, plain, and correct meaning to the creation story, we show that non-literal interpretations can in fact arrive at firm, correct conclusions, and cannot be used to say whatever we want.

Now, none of this is to say that the above meaning is the only meaning in the story, or to even say that additional meanings are not important. If I had intended to say that, I would not be writing this whole thing on how the Genesis creation story should be interpreted. There is certainly much more to be discovered about the meaning in Genesis 1. Some of the better known non-literal approaches are the framework interpretation, and the metaphorical interpretation at the end of Saint Augustine's "Confessions". Of course, there's much more to be said about the "bread of life" metaphor, too. We shouldn't stop trying to understand more about the Bible just because we found the simplest level of understanding. So all these interpretations, along with the purely literal interpretation, should be considered, weighed, and rejected or accepted, yet we must do so without losing sight of the simple essential meaning of the Genesis creation story.

This now brings us out of the creation week, and to the central couple in the creation story.

Adam and Eve were historical persons. Who were they?

Adam and Eve were exactly who the Bible says they were: humans created in the image of God, having been endowed with a living soul by God's breath. They are the ancestors to all humans alive today. Through them, we too bear the image of God, but we're also impacted by their sin and its consequent curse.

As such, they are of seminal importance in understanding our spiritual history, and form the crucial component in the Genesis creation story and my interpretation of it. Now, as I've said before, Genesis 1:1-2:3 uses a broad, abstract, metaphorical language befitting its placement as the prologue to the whole Bible. But starting with Genesis 2:4, the language settles down to the matter-of-fact style used for the remainder of Genesis, and the stories thereafter should be interpreted "literally". So, Adam and Eve were historical persons. They lived in a physical Garden of Eden, where they ate a real fruit, after being deceived by a snake that actually talked.

At this point it's important to remember what the Bible does NOT say about Adam and Eve. These are common but unfounded assumptions that people often read into the story, assumptions which in fact cannot be true based on our understanding of history and science. So: the Bible does NOT say they were the first members of the species Homo sapiens sapiens. That is a designation that did not even exist until modern taxonomy, and it would be ridiculous to use it in our interpretation of Genesis. The Bible also does NOT say that they were the only anatomically modern humans God created. It actually often hints at the existence of other humans outside their family. The Bible only says that Adam and Eve were the ones to be created in the image of God. I am here making a very clear distinction between biological humans and spiritual human beings. Biological humans evolved around 300,000 years ago, according to our current best estimates, but Adam and Eve lived some 6,000 to 12,000 years ago, depending on how you interpret the genealogies. Adam and Eve were not the first biological humans or the only ones that lived in their time, but they were the first complete spiritual human beings - biological humans who were also ensouled bearers of the full image of God.

You may object that I have divided the human race into two classes: "spiritual human beings" and mere "biological humans", which I suppose can be termed "mere animals" if one were in an inflammatory mood. I will come back to this point later, but for now, it is of little practical importance. Everyone you meet, every individual you've read about, everyone that appears in the Bible or in history, and every person that you've ever felt a human connection to, are all descendants of Adam and Eve, and all spiritual human beings. This distinction therefore cannot be used to justify any kind of discrimination or oppression.

But what happened to this race of non-Adamic biological humans? Did they die out? No, their biological progeny continues, and they're doing very well. They were fully biologically human, after all. Characters in the Bible like Cain's wife, or Seth's wife, came from this group of people. Like with Cain and Seth's wives, they all eventually mated with descendants of Adam and Eve, and thereafter their children are counted among the spiritual human beings. This process continued on, until the entire human population is now descended from both the biological humans, and also Adam and Eve. Since they far outnumbered the two people living in the Garden of Eden at the time, our biological heritage - our genes - comes mostly from this group of people. But our spiritual heritage comes from Adam and Eve.

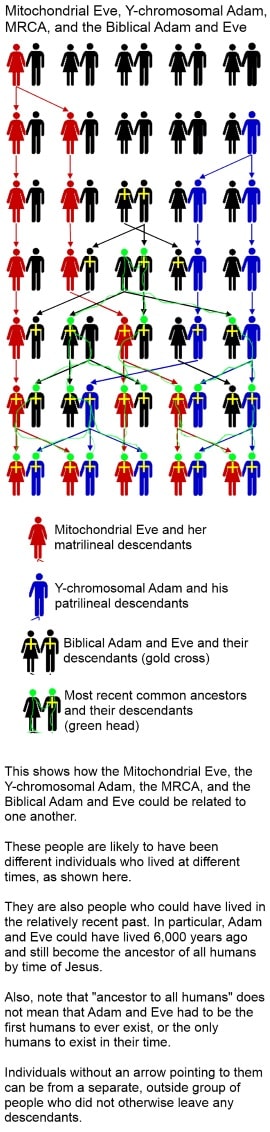

But how could Adam and Eve be ancestors to all the humans alive, if they only lived 6,000 to 12,000 years ago? Isn't this all rather contrived? Not at all. It is actually perfectly natural for a population to have a relatively recent common ancestor. It would be contrived if such a common ancestor did not exist - That would basically mean that the "population" was in fact two or more populations. And the scientific time estimates for the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) for all humans is shockingly recent - possibly as little as 2,000 to 4000 years ago by some estimates. Needless to say, this timeframe agrees remarkably well with the biblical timeframe for Adam and Eve.

This discovery of a recent common ancestor is relatively new but well-established science. I will illustrate the all the important points below as they come up, but you should still understand the bigger picture, and know that none of this is something that I'm just making up. You can check out the Wikipedia article on the subject, the original Nature paper that it cites, or S. Joshua Swamidass's book for more information.

So humanity could have biologically started 300,000 years ago, yet really have a recent common ancestor as little as 2,000 years ago? Absolutely. Consider this simplified example: there is an isolated village in the mountains, numbering several hundred individuals. They have been around for a thousand years, isolated from everyone else and marrying among themselves. But one year, all their menfolk die, due to some sex-selective plague, or perhaps a catastrophe at a village-wide male-only ritual. Now it looks like the village will die out from the failure to reproduce. But one man, an outsider, wanders upon the village and settles there. He then dutifully impregnates all the women of the village for a generation, until his sons could take over, and the village is saved from extinction.

So the village existed for a thousand years, yet the most recent common ancestor of the village was this man from the outside, in just the last generation.

How about a more realistic example? The descendants of Genghis Khan are said to number in the tens of millions, and that's just counting the men along the patrilineal (father to son) line. They form a nontrivial fraction of the entire world population. You can easily imagine that in another millennium, this group of people will move around, mix, and marry other people, to the point that everyone in the world will be a descendant of Genghis Khan.

At this future point, the human race would still be some 300,000 years old, but their MRCA would be Genghis Khan, who would have lived less than 2000 years ago. Also, this would not imply that Genghis Khan and his mates were the only people to exist in their time, or the only ones to contribute to the gene pool of the world population. In fact, even with Genghis Khan being the MRCA, his genetic contribution to any given individual at this point would be quite small or nonexistent (as a "genetic ghost"), as it went through many intervening generations where it was mixed and diluted with other people's genes.

So, Adam and Eve were a recent common ancestor (RCA) to the human race. Note that they don't necessarily have to be the MOST recent common ancestor (MRCA); they could have been an ancestor to the MRCA, for instance. Note also that the biblical Adam and Eve are almost certainly not the mitochondrial Eve or the Y-chromosomal Adam. These individuals are the ancestor to only the members of their own sex, following only the matrilineal or patrilineal lines. This is a strong restriction on leaving descendants: for instance, if a couple only had a son, who then only had a daughter, this would break both the matrilineal and patrilineal lines, whereas the MRCA could still trace their descendants through this line. Because of this same-sex restriction, the lines of ancestry for mitochondrial Eve and the Y-chromosomal Adam converge far too slowly, making these individuals far older than the MRCA and too old to be the biblical Adam or Eve.

Lastly, there is the question of when, exactly, Adam and Eve became the common ancestor to the whole world. As I mentioned above, I believe that every person in the Bible, and everyone that we have a written historical record of, is a descendant of Adam and Eve. This means that their descendants had to spread to each of the major civilizations before it began to flourish, and probably spread out to nearly everywhere by the time of Christ.

This is a strong constriction which forces back the possible dates for the required common ancestor. Yes, the MRCA of 21st century humans only lived 2000 to 4000 years ago, but perhaps that's only due to the relative ease of modern travel allowing more people to mix? How much further back would we need to look to find the MRCA of the people in the first century? The starting point would be pushed back 2000 years, and travel was more difficult - would a biblical Adam and Eve be old enough?

These possible difficulties and implications, along with one major modification to this model that I have not yet mentioned, will be elaborated on in the next sections. But for now, this is the skeleton outline of my model: Adam and Eve were recent common ancestors to all the humans who lived at the time of Jesus. Thereafter, all of us - all humanity - are their descendants. We inherit our spiritual condition from them, both the image of God and the effects of the original sin. Big Bang and human evolution all took place, but they happened far before Adam and Eve.

I believe that, with the modifications that I'll discuss in the next section, this model squares with all the relevant scientific, historic, and biblical facts. In fact the agreement between the biblical date for Adam and Eve, and the historical/scientific dates for recent common ancestors, is quite good.

The relational propagation of the image of God

So, Adam and Eve were recent common ancestors to all of humanity. This means that they were almost certainly NOT the first humans, or the only humans to have lived in their time. Instead, they were the first humans to have been ensouled by God and created in his image. As their descendants, we too bear the image of God, but are also affected by their original sin. This model accounts for everything the Bible says about Adam and Eve, as well as all known history and science.

Now in the previous section, I said that I will be making one major modification to my model, and mentioned that I will come back to the issue of "merely biological humans" - people who were not directly descended from Adam and Eve, and possibly do not bear "the image of God".

The modification is about these non-Adamic humans. To be frank, the existence of this group of people - whom you may be tempted to call 'soulless' or 'animals' or 'sub-human' if your intent was to degrade them - is the issue in my theory that bothers me the most. But remember that this issue has no practical consequences: I think the descendants of these non-Adamic humans have long been thoroughly mixed with the descendants of Adam and Eve, so that everyone alive now is fully human. Therefore this issue cannot be used to justify any kind of oppression or discrimination.

But how about in history? Well, I believe that Adam and Eve became common ancestors to humanity early enough, so that anyone you read about in history, or anyone recorded in the Bible, is still their descendant and therefore fully human. So this issue of non-Adamic humans also cannot justify any kind of historical oppression, even the ones that happened thousands of years ago.

But didn't the descendants of Adam and Eve interact with these people at some point in prehistory? Doesn't my model, in fact, require many rounds of sex and child-rearing between the fully spiritual humans and their non-Adamic counterparts, so that their descendants could be brought into Adam and Eve's lineage? Well, yes. What happened in these interactions?

Let's look at a specific scenario: what would happen if a full human adopted a non-Adamic child? Say that Adam and Eve came across a lost baby and took him in as their own, out of compassion and pity. Would this child then be fully human? Would God grant him a soul, and would he bear the image of God?

This is fundamentally a question of how the soul, or the image of God, is propagated from person to person. Up until now, we have been working under the implicit assumption that it's transmitted the same way that genes are - by biological parentage. But is that really how it works? This is not a question that can be definitively answered, but several lines of biblical reasoning suggest the answer is "no".

First, none of the other spiritual qualities propagate that way. For example, sin doesn't propagate that way. The Bible says that "bad company corrupts good character". God also commands Israelites to not even make treaties with the Canaanite nations that he's driving out before them, because their ways were evil and infectious. Both are examples of sin propagating through non-biological means. Even in our day to day lives we see that sin propagates through human relationships, rather than just from parent to child.

The new life we have in Christ also doesn't propagate that way. Faith comes through hearing the word of God preached. Again, the medium of propagation is the connection from one person to another, the relationship between two people. It does not necessarily follow genetic lineage. Of course, our parents are the people who influence us the most, and both our sins and our faith are most often transmitted to us through them. But we should not confuse this for biological heredity.

Also, consider that Luke, in his genealogy, says Adam was the "son of God", in exactly the same way he says that Seth was the "son of Adam". The same genealogy also says that Jesus was the "son of Joseph". Obviously, these father-son relationships are not based on a biological connection. But this genealogy is the same one that's in Genesis - the one that traces the descendants of Adam. In fact, the genealogy in Genesis begins by explicitly invoking the image of God, and connects it with Seth being a likeness and image of Adam, clearly implying that the image of God propagated from Adam to Seth. It is this very method of propagating the image of God that Luke expands to include non-biological fatherhood.

This is clearly spelled out in John 1:13. Being the "children of God" does not depend on "natural descent" or a human parent's biological decision. Now, there can be some hair-splitting of the difference between "children of God" and "image of God", but overall I believe that this is fairly convincing evidence that biological heredity is not essential for our spiritual identity.

All these things suggest that the image of God is transmitted, not through purely biological means, but through relationships - in particular, the kind of nurturing, mentoring, teaching, and influencing relationship that a father would have with his son, born out of love. This most often happens between parents and their biological children, but the biology only exists to serve the relationship. God, as the one from whom all fatherhood on heaven and on earth derives its name, saw fit to design our biology to enable the relationship, so that we could better understand and draw near to him.

So yes, a non-Adamic child adopted by Adam and Eve would inherit the image of God, and become a full human being. In fact, I believe that any relationship born of love, where one person shapes the identity of the other through that love, can serve as a conduit for propagating the image of God. As I said, this most often happens between parents and their biological children, but it can also happen between parents and an adopted child, a teacher and a student, a master and an apprentice, a commander and his soldiers, or between spouses, depending on the circumstances. Through all relationships of this kind, the image of God propagated throughout the human race over time.

At this point, you may say, "isn't this a lot of improbable speculations just to get your theory to work? Why doesn't the Bible explicitly mention any of this?" First, I don't think this is improbable. The main idea, that the image of God - the essence of our spiritual identity - is propagated through relationships, is a simple idea with solid biblical backing, as I documented above. I do admit that there is some speculation, and that the Bible doesn't explicitly endorse this view. But before you use these as reasons to dismiss the theory, consider the following:

By now, you may have noticed the parallel between the question of the non-Adamic people, and that of the "unreached people groups". What is the status of the people who never hear the Gospel? Are they, or can they be, saved? What degree of faith in God, or in Jesus Christ, do they need? What if they lived before Christ? Does it matter? What if they only heard a poor presentation of the Gospel once in passing? These are important questions, and answering them necessarily involves some speculation. Yet the Bible doesn't explicitly speak on the issue, despite its importance.

Why? Because the Bible instead gives us a commandment that's far more simple, practical, and effective. Rather than going into some esoteric discussion about the salvation status of unreached people groups, it simply tells us to make disciples of all nations. Following this commandment makes the discussion about unreached people moot. Are they unsaved? Go, preach the Gospel to them, so that they may be brought to salvation. Are they saved? Go, preach the Gospel to them, to bring them into a better understanding of the salvation they have. The question about unreached people is of no practical consequence, in light of this commandment we're given to obey.

The same is true for the question of non-Adamic people. The Bible doesn't discuss the question explicitly. Instead, God tells us to love our neighbors, which is a far more simple, practical, and effective course of action. It is also one of the oldest and best-known moral laws, discernible even by the ungodly, even before the law of Moses. In obeying this law, the question of non-Adamic people would have been rendered moot. How should these outsiders be treated? Could they even be distinguished from the "fully human" children of Eve? It didn't matter - none of it was of any practical consequence. The children of Adam and Eve were to love these outsiders anyway, and in doing so, they would have naturally passed on the image of God, turning these biological humans into fully spiritual human beings. In bearing the image of God who freely made them in his likeness, they would freely pass on that likeness to all those they came across.

Now, did the descendants of Adam and Eve actually obey this moral imperative? Not really. Overall, they were probably no kinder to these outsiders than we are to one another. In fact, the two groups of people probably became indistinguishable several generations after Adam and Eve, so their cruelties upon one another were probably just ordinary human cruelties. But in acting so, they were violating God's moral law, even if the offense was against non-Adamic people. So, even in the early, prehistoric days, when the two groups of people both existed and could theoretically be distinguished, there would have been no justification for discrimination or oppression.

And with this understanding, we can even tackle potential modern difficulties. Say that we discover an isolated people who are not descended from Adam and Eve. Say that we somehow knew for certain that they were "merely biological humans". This is all pretty much impossible, but let's pretend that it's true for a moment. Could we then oppress or exploit them, since they are not fully human? Absolutely not. Instead we are to love them as our neighbor, as we love ourselves. We are to teach, guide, and empower them, thereby enabling their incorporation into the rest of humanity. We are to preach the Gospel to them. We are to do this with all due respect for their culture and their right to self-determination. We will thus impart the image of God onto them, making them fully our equals.

Why? Are they not merely animals? Something similar could be said of Adam, the origin of our own full humanity - he was merely dust. God did not give Adam a soul because Adam was worthy, but instead to make him worthy. Christ died for us while we were still sinners. We rightly say that humans have value because we bear the image of God. Then, as God's image, we are to imitate him, who gave out that same soul-granting image to unworthy piles of dust, to lowly sinners. Freely we have received; freely give.

We Americans have a well-known line in our Declaration of Independence: "all men are created equal". The idea is that SINCE we are all equal, we ought THEREFORE to be treated equally by the government, in our rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. As political ideas go it's not terrible, but it falls far short of the glorious grace of the Gospel, of the God who saves sinners and declares them all to be one in Christ. The idea is that EVEN IF we are inherently unequal to begin with, and all undeserving, he will STILL lift us all up to be one in Christ. That is the God we are to imitate, the God whose image we bear.

So, that settles the question of these non-Adamic humans once and for all. At no point in time or space is there ever a justification for using the distinction between "mere biological humans" and "descendants of Adam and Eve" for oppression or exploitation. Since the image of God is propagated through any archetypal father-son relationship, where one person shapes the identity of the other in love, the proper response by the descendants of Adam and Eve would have always been to love and grow the "biological humans", to thereby impart the image of God upon them.

An aside on the image of God

But even with all that, people will want to speculate on the exact status of these non-Adamic humans. I have made it clear that this question is irrelevant, as it cannot possibly apply today and could have never made any difference in anyone's duty to treat such people with love and respect. But still, given that speculations are inevitable, we might as well explore it a bit, especially since it gives us a chance to expound on a key idea in Genesis - the "image of God".

Of course, the "image of God" is a momentous idea, and I cannot cover it fully here. Even if I could, the question of non-Adamic people is quite uncertain by its nature. So what I say here will not contain any full or firm answers, but I think we can still extract some good principles.

I believe that God imparts some of his image on everything he creates. C.S. Lewis says as much in Mere Christianity, explaining that even empty space is like God in its hugeness. Above and beyond that, I think certain physical things have an intrinsic, structural capacity to bear the image of God. So while empty space is mostly lacking this capacity, a book has more potential, and a computer program greater potential still. A complete human being has the greatest potential of all: in fact, we know that it’s perfectly sufficient, because it was made specifically for that purpose: to bear not just any image of God, but God himself, in the Incarnation. If humanity is singled out or considered unique in bearing the image of God, this is the reason why.

Now, as God’s image bearers, we all have a duty to be like him, to the extent that we are able. So like God, we are to emit the image of God to all that we create, influence, or beget, to the fullness of the recipient’s potential.

This gives us an excellent guiding principle - not just on the matter of non-Adamic people, but for all kinds of questions we may encounter in the future.

So: can we exploit non-Adamic people, if they existed today? Absolutely not. They're fully capable of receiving the image of God, and we have a moral duty to impart it to them. Thereafter they become our equals, and we are to treat them as such.

Can we exploit farm animals, for food, materials, or labor? Well, they're not capable of receiving the full image of God - but even to them, we are to impart it to the extent that we are able, to the limits of their capacity. This then prohibits senseless cruelty or needless slaughter of such animals, but it allows for them to be sacrificed for our sustenance, to better maximize something like the 'total image of God in the system'. Meanwhile, we are to look for ways to help these animals - to better understand and care for them, reduce their suffering, and increase their overall capability for the image of God. But of course, such things have to be constantly balanced against other things we can do with our finite capacity, like respecting the image of God in a fellow human who’s going hungry.

How should we treat our pet dogs or cats? Or how about a more intelligent animal, like an elephant or a dolphin? Again, they're not capable of receiving the full image of God, but we are to impart it to them to the extent of their intrinsic capacity, and value them accordingly. And I think it's pretty clear that we can be quite successful in this endeavor: our dogs can really be good, or really bad. The same mandate which requires us to emit the image of God to other humans demands that we do the same to our pets, that we should try to make our dogs "good boys" or "good girls".

What if we develop 'true AI', whatever that means? Or what if we meet space aliens who seem as intelligent as we are? The answer is the same: impart to them the image of God, to the extent that we are able and they are capable of receiving. We then prioritize the total system to maximize this image of God.

In Isaiah’s vision, the seraphim that stand around God’s throne call out to EACH OTHER, and say, "holy, holy, holy is the Lord Almighty; the whole earth is full of his glory." Meaning (I think), they’re constantly revealing and receiving the image of God to and from one another, in a way that each individual is uniquely capable of revealing and receiving.

So how does this all apply to the question of non-Adamic people? In accordance with everything I've said above, I think it's clear that such people:

- have the image of God to some extent,

- are capable of receiving it to the full extent,

- are lacking some part of the full image of God, in comparison to Adam,

- and are also missing Adam's original sin - that particular marring of the image of God that resulted from him eating from the forbidden tree.

I again remind you that the exact status of the "image of God" in such people is irrelevant for any practical reason, and could never have justified any kind of discrimination or oppression at any point in time. My previous arguments for the fair treatment of such people would still operate with full force, even if the "image of God" had been initially completely absent from them: any descendant of Adam and Eve, upon meeting such an individual, had the moral duty to impart the image to them, regardless of their previous status. And because they are capable of receiving it fully, they would have been thereafter made into complete, spiritual human beings - also "descended" from Adam, also bearing the full image of God, and fully our equals.

The worldwide propagation of the descendants of Adam and Eve

To summarize: Adam and Eve were not the first humans, or the only humans to live in their time. Instead, they were the first ones to be made in the full image of God, and they eventually became recent common ancestors to all of humanity. "Ancestors" here should be understood in the spiritual sense: we inherit from them both the image of God and the effects of their original sin. Because this is a spiritual heritage, its propagation is not limited to biological reproduction. It can be transmitted through any loving relationship that shapes the identity of the beloved. This most commonly takes place between parent and child, but it can also happen in any other analogous relationship.

Given this mechanism, how might the spiritual descendants of Adam and Eve have spread throughout the Earth?

Adam and Eve were exceptional spiritual beings: they had literally spoken with God. They were furthermore created in a spiritual vacuum: everyone else around them lacked their fullness in the image of God. In such circumstances, Adam, Eve, and their descendants would have wielded great influence among the surrounding people, allowing them to bear many spiritual children. Their spiritual descendants might have far outnumbered their biological children. The image of God would have therefore spread very quickly among their neighbors, turning them into fully spiritual human beings. They, in turn, would further transmit the image of God with similar ease - and much like the rapid propagation of Christianity in its early days, the descendants of Adam and Eve would have spread like wildfire throughout humanity.

This process would have been aided by the many mundane advantages that come with their full humanity. Their new spiritual condition would have infused and influenced their descendants throughout the generations, and manifested itself even on a material level. For instance, the descendants of Adam and Eve may have had a more just form of government, or sacrificed more for the common good. They would have been culturally superior to the other biological humans. For a modern analogy, think about the difference between North and South Koreans: same genetic stock, but drastically different cultures, resulting in different levels of physical well-being. In this way, the benefits of knowing God would have flowed from their spirits even down to the prosaic matters. So the descendants of Adam and Eve would have been healthier, wealthier, wiser, more inquisitive, more respected, and more well-liked.

Even when they turned to evil due to the corrupting influence of the fall, their effectiveness in propagation would have been hardly diminished. Such a people would still maintain much of their power that came from their spiritual awareness. For instance, they might have been more domineering in their foreign relations, more ruthless in conquest, and more efficient in oppression. They would have been more brutal in imposing their will, their culture, and their progeny upon their neighbors. For good or ill, the descendants of Adam and Eve would have been able and effective. All this would have naturally enhanced their fecundity, through both biological reproduction and spiritual relationships.

Then there's the issue of long lifespans in the genealogies of Adam's line. I am undecided on how to interpret them: they may be numerological, or real, or real but with gaps, or maybe something else altogether. If real, maybe all antediluvian biological descendants of Adam and Eve enjoyed phenomenal longevity. Or maybe these lifespans only applied to the male heirs in the messianic line. In any case, whether you take the numbers literally or as an expression of the fact that these were remarkable, important men, the net effect for the descendants of Adam and Eve would be to further enhance their fecundity.

On top of all that, Adam and Eve, and later Noah and his family, are divinely charged to 'be fruitful and multiply'. Additionally, there are multiple events in the early chapters of the Bible which scatters the children of Adam and Eve - such as Cain's exile, the confusion of tongues at the Tower of Babel, and the calling of Abraham away from his homeland. All of this would have had the net effect of quickly spreading out Adam and Eve's descendants, drastically reducing the time necessary for them to become the spiritual common ancestor to all of humanity.

What implications does all this have in terms of the validity of my theory?